Native Bird Species at Flight 93 National Memorial

-

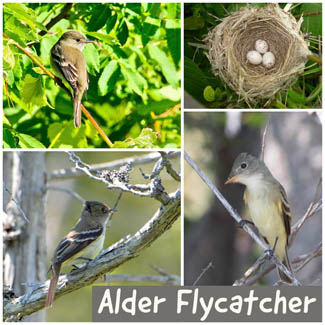

Alder Flycatcher -

American Crow -

American Goldfinch -

American Kestrel -

American Redstart -

American Robin -

American Tree Sparrow -

American Wigeon -

Bald Eagle -

Baltimore Oriole -

Bank Swallow -

Barn Swallow -

Barred Owl -

Belted Kingfisher -

Black-capped Chickadee -

Black-throated Green Warbler -

Black Vulture -

Black-and-white Warbler -

Black-billed Cuckoo -

Blackburnian Warbler -

Black-throated Blue Warbler -

Blue Grosbeak -

Blue Jay -

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher -

Blue-headed Vireo -

Blue-winged Teal -

Bobolink -

Broad-winged Hawk -

Brown Thrasher -

Brown-headed Cowbird -

Canada Goose -

Cape May Warbler -

Carolina Chickadee -

Carolina Wren -

Cedar Waxwing -

Chestnut-sided Warbler -

Chipping Sparrow -

Cliff Swallow -

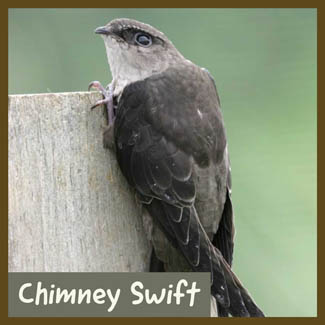

Chimney Swift -

Common Grackle -

Common Raven -

Common Yellowthroat -

Cooper's Hawk -

Dark-eyed Junco -

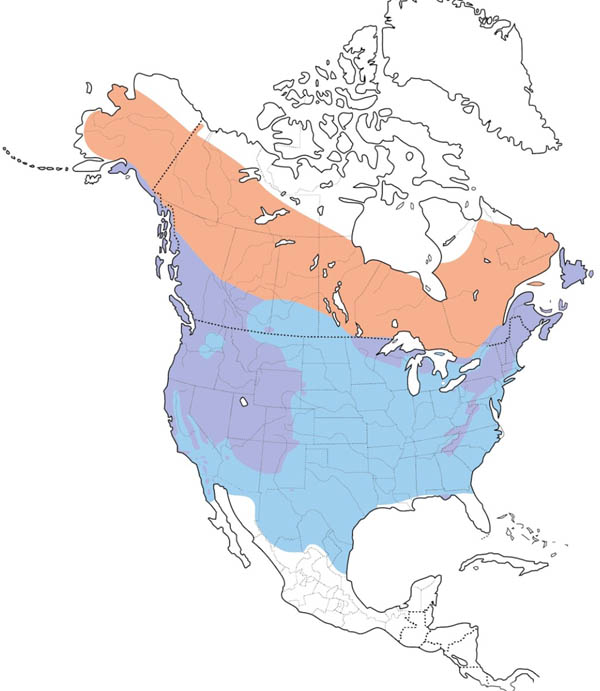

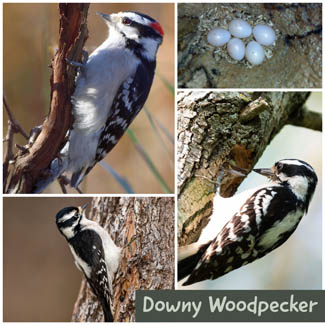

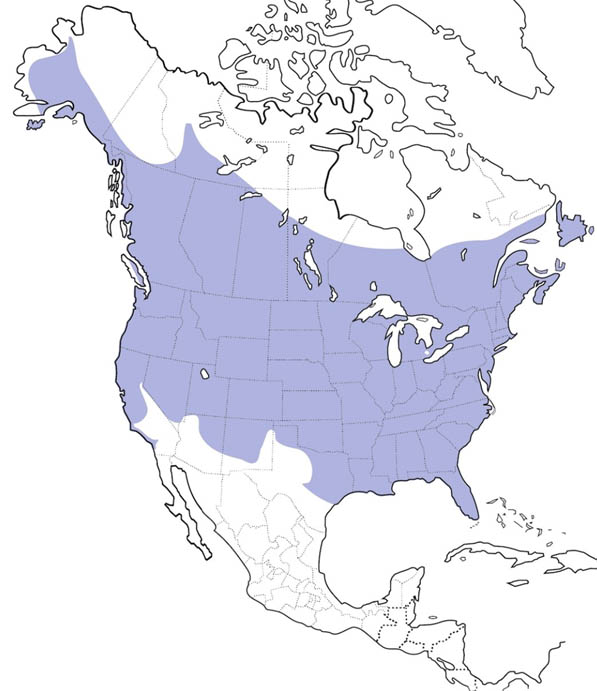

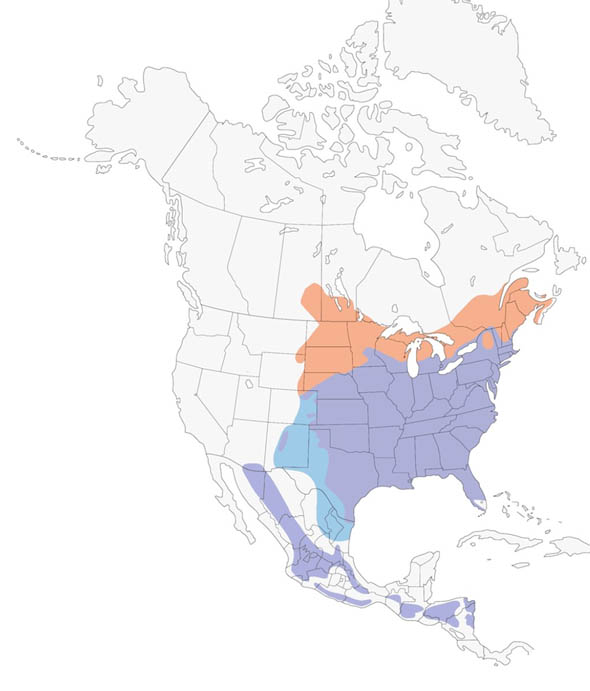

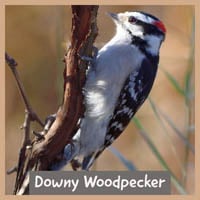

Downy Woodpecker -

Eastern Bluebird -

Eastern Kingbird -

Eastern Meadowlark -

Eastern Phoebe -

Eastern Towhee -

Eastern Wood-Pewee -

European Starling -

Field Sparrow -

Grasshopper Sparrow -

Gray Catbird -

Great Blue Heron -

Great Crested Flycatcher -

Great Egret -

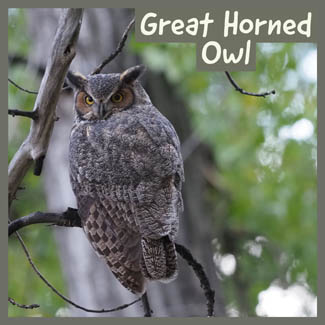

Great Horned Owl -

Greater Yellowlegs -

Green Heron -

Hairy Woodpecker -

Henslow's Sparrow -

Hooded Merganser -

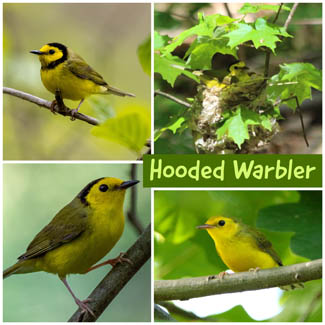

Hooded Warbler -

Horned Grebe -

Horned Lark -

House Sparrow -

House Finch -

House Wren -

Indigo Bunting -

Killdeer -

Least Flycatcher -

Least Sandpiper -

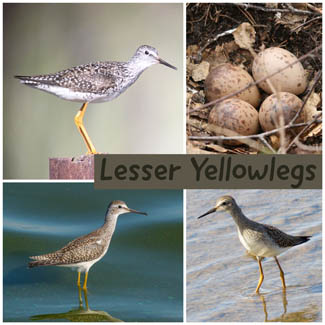

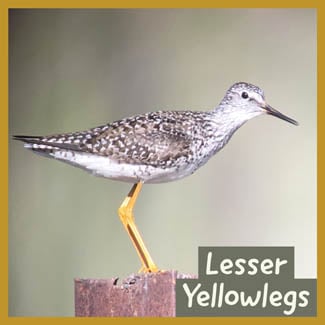

Lesser Yellowlegs -

Magnolia Warbler -

Mallard -

Mourning Dove -

Northern Cardinal -

Northern Flicker -

Northern Harrier -

Northern Parula -

Northern Mockingbird -

Northern Rough-winged Swallow -

Northern Shrike -

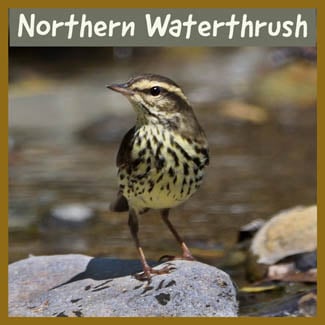

Northern Waterthrush -

Ovenbird -

Osprey -

Palm Warbler -

Peregrine Falcon -

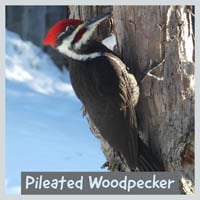

Pileated Woodpecker -

Prairie Warbler -

Purple Finch -

Red-bellied Woodpecker -

Red-eyed Vireo -

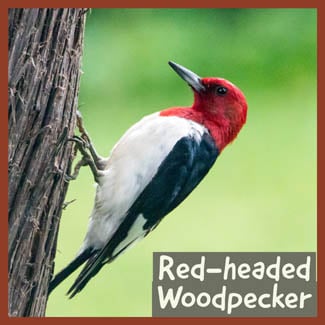

Red-headed Woodpecker -

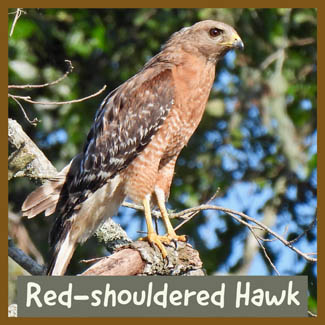

Red-shouldered Hawk -

Red-tailed Hawk -

Red-winged Blackbird -

Ring-billed Gull -

Ring-necked Duck -

Ring-necked Pheasant -

Rock Pigeon -

Rough-legged Hawk -

Rose-breasted Grosbeak -

Ruby-crowned Kinglet -

Ruby-throated Hummingbird -

Ruddy Duck -

Sandhill Crane -

Savannah Sparrow -

Semipalmated Plover -

Semipalmated Sandpiper -

Scarlet Tanager -

Sedge Wren -

Sharp-shinned Hawk -

Short-eared Owl -

Snow Bunting -

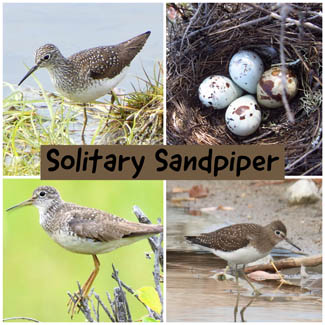

Solitary Sandpiper -

Song Sparrow -

Spotted Sandpiper -

Swainson's Thrush -

Swamp Sparrow -

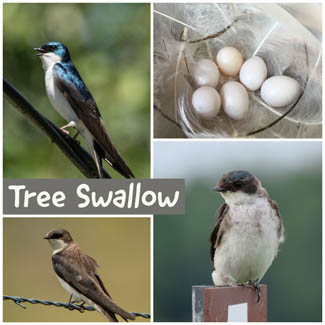

Tree Swallow -

Tennessee Warbler -

Tufted Titmouse -

Turkey Vulture -

Upland Sandpiper -

Vesper Sparrow -

Warbling Vireo -

White-breasted Nuthatch -

White-eyed Vireo -

White-throated Sparrow -

Wild Turkey -

Willow Flycatcher -

Wilson's Warbler -

Winter Wren -

Wood Duck -

Wood Thrush -

Yellow Warbler -

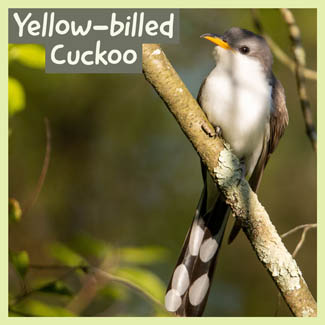

Yellow-billed Cuckoo -

Yellow-rumped Warbler

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Jack & Holly Bartholmai / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML243673741)

- Female: Michael J Good / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML165563711)

- Juvenile: Tony Leukering / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML67545601)

- Nest/Eggs: Jim Lind / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML36734141)

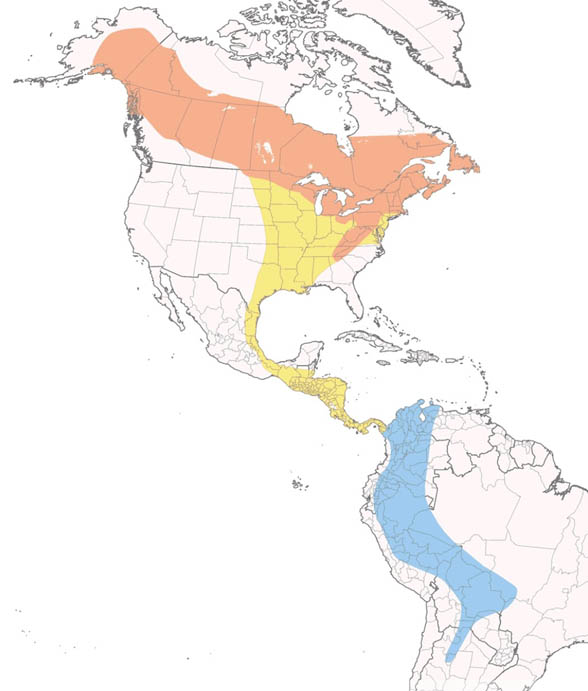

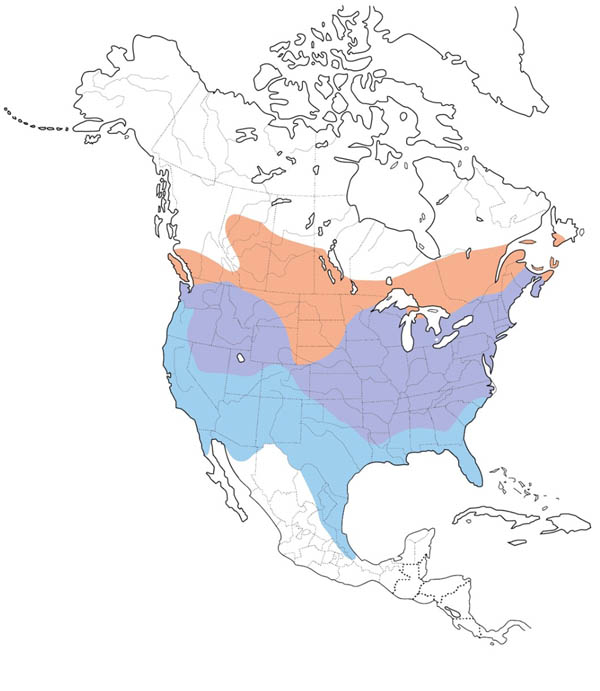

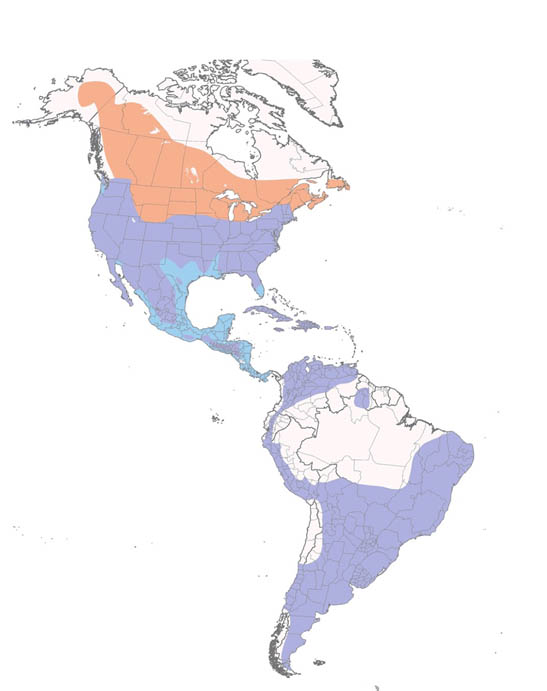

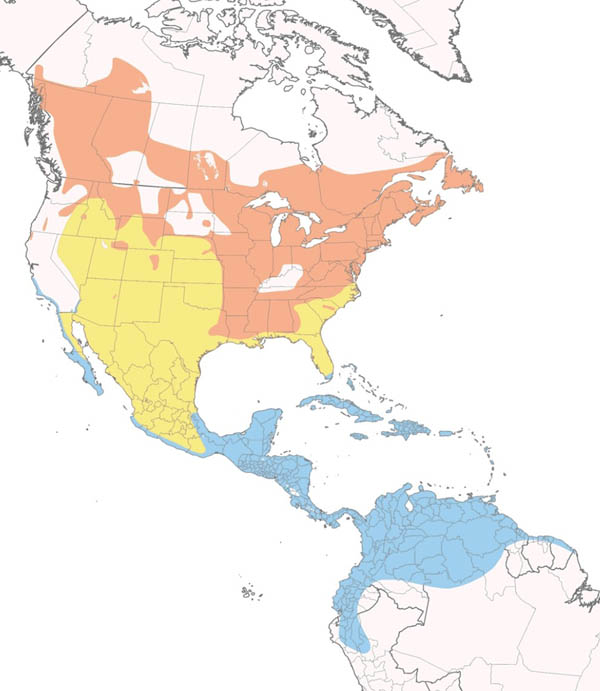

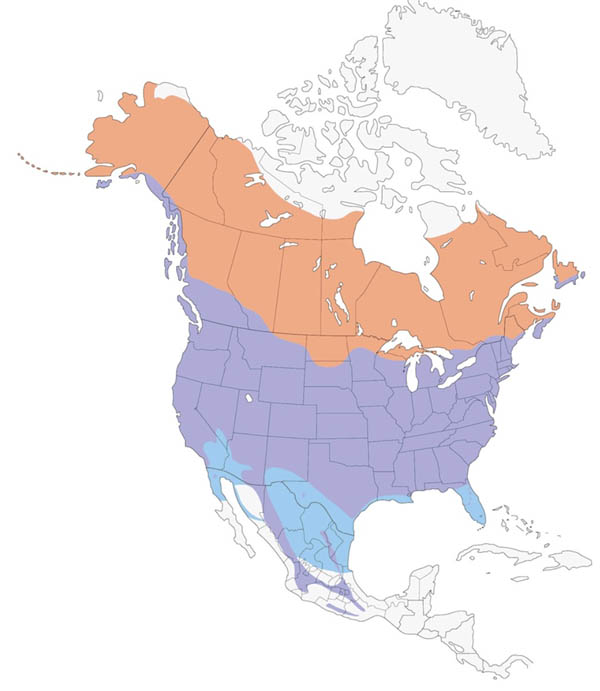

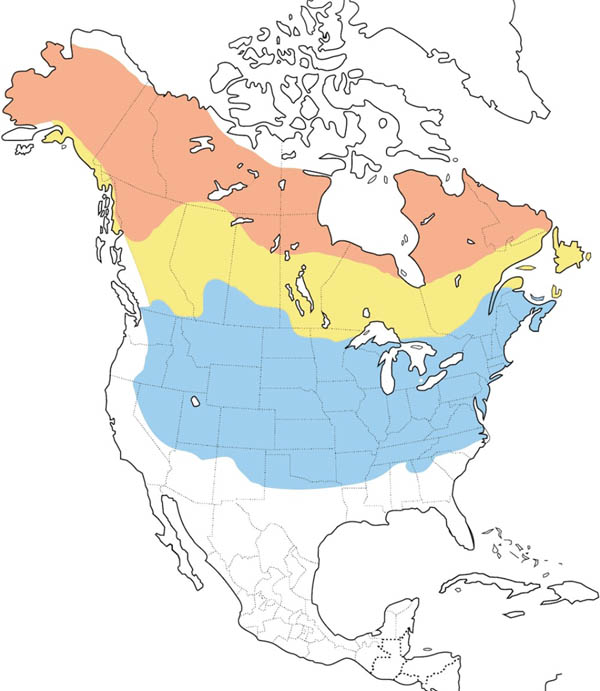

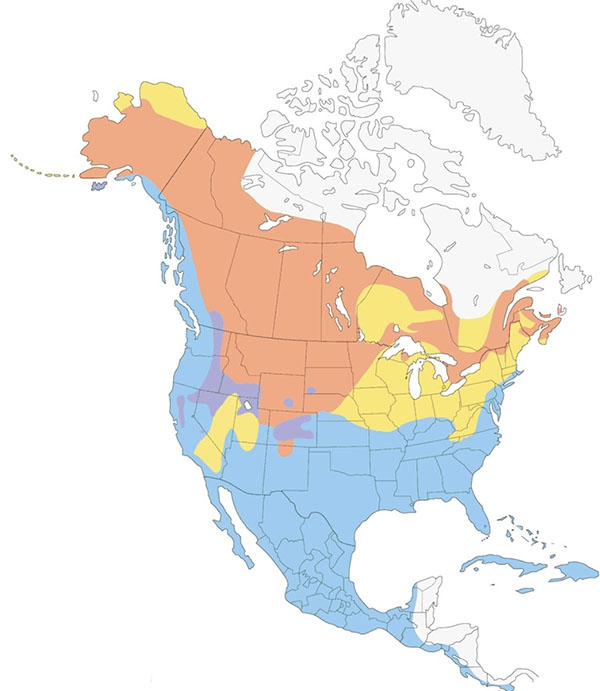

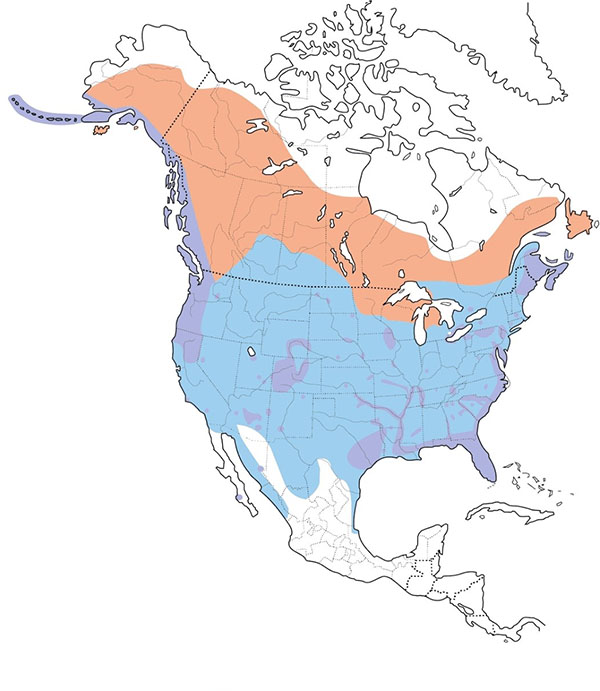

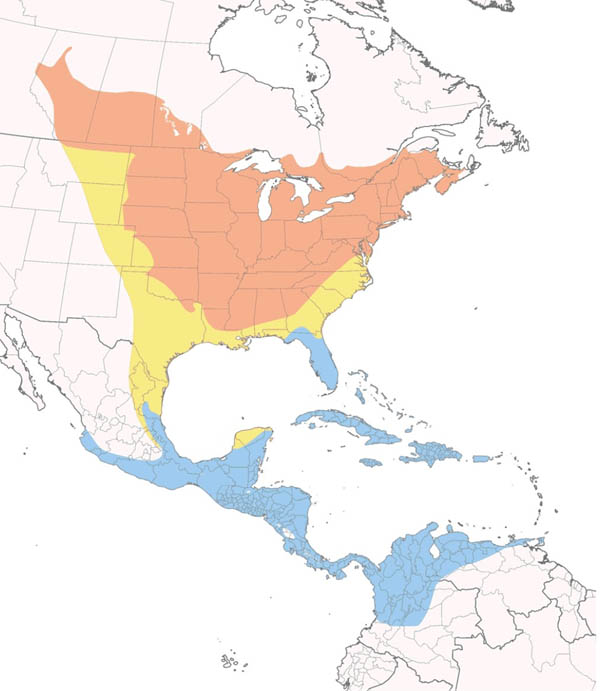

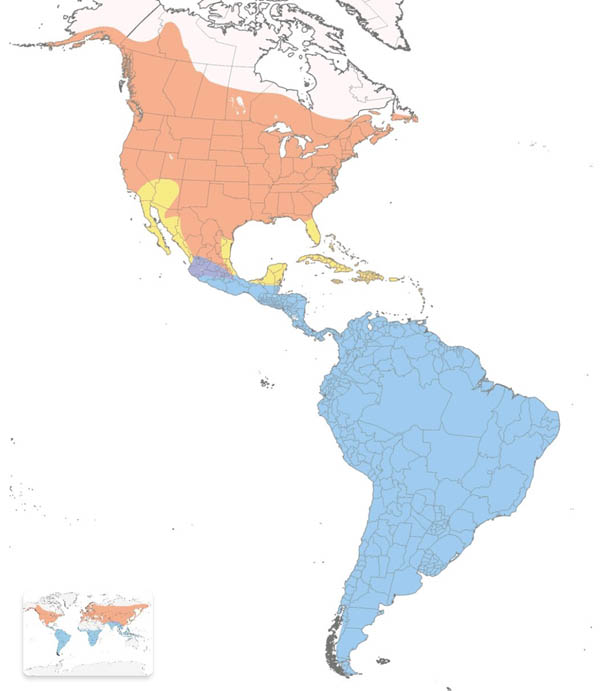

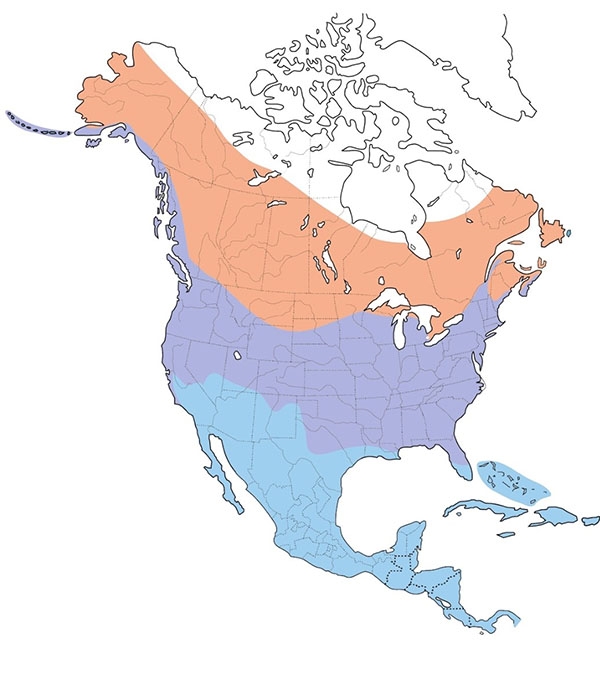

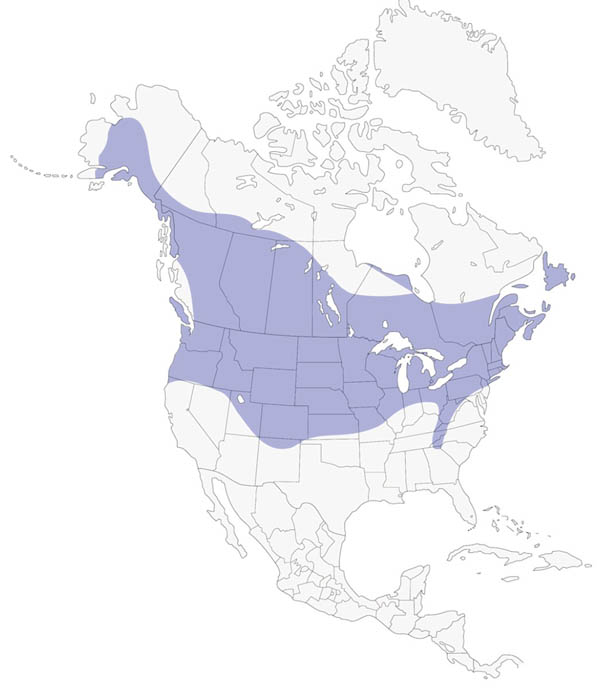

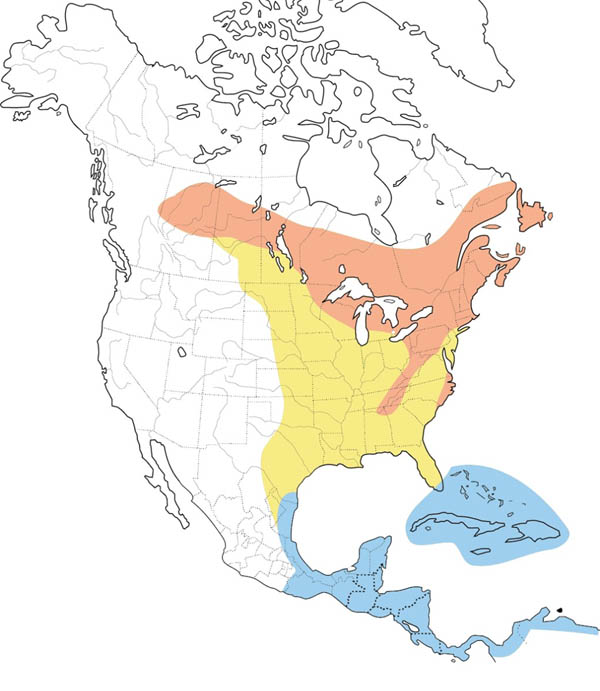

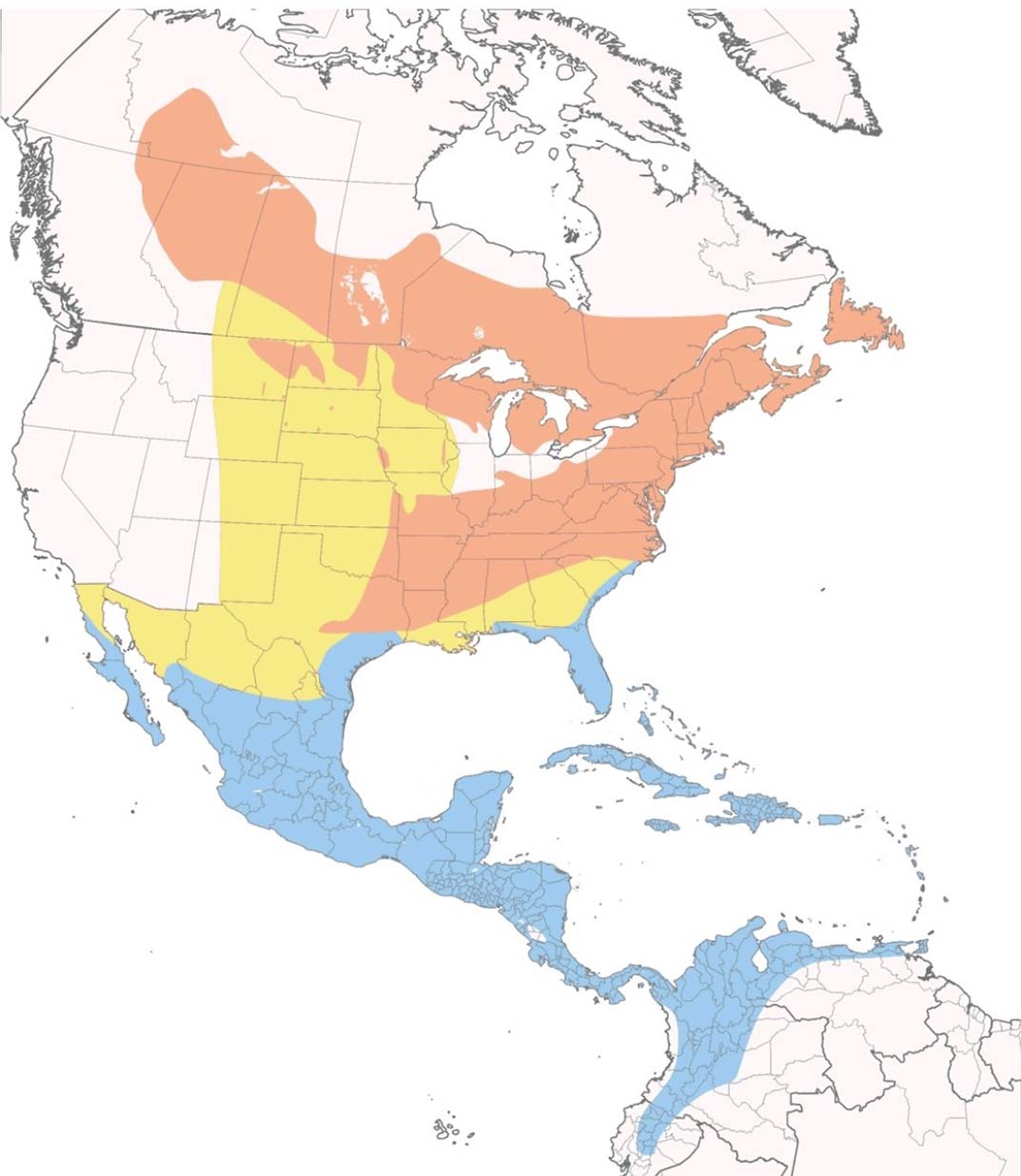

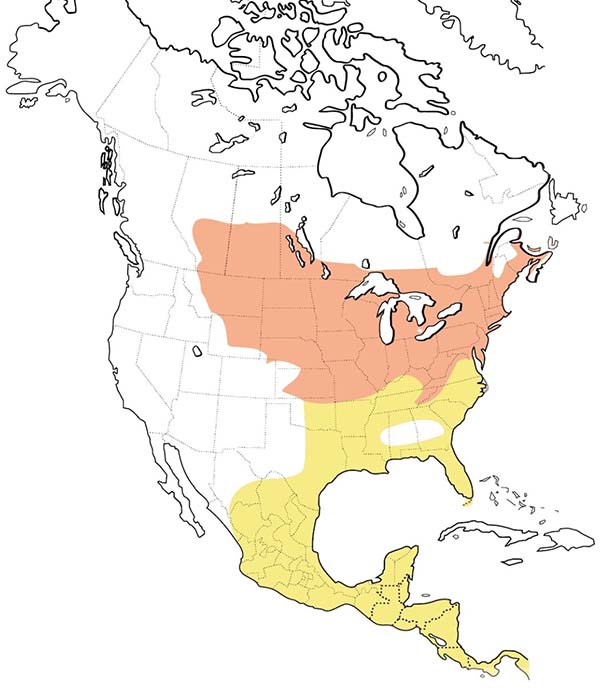

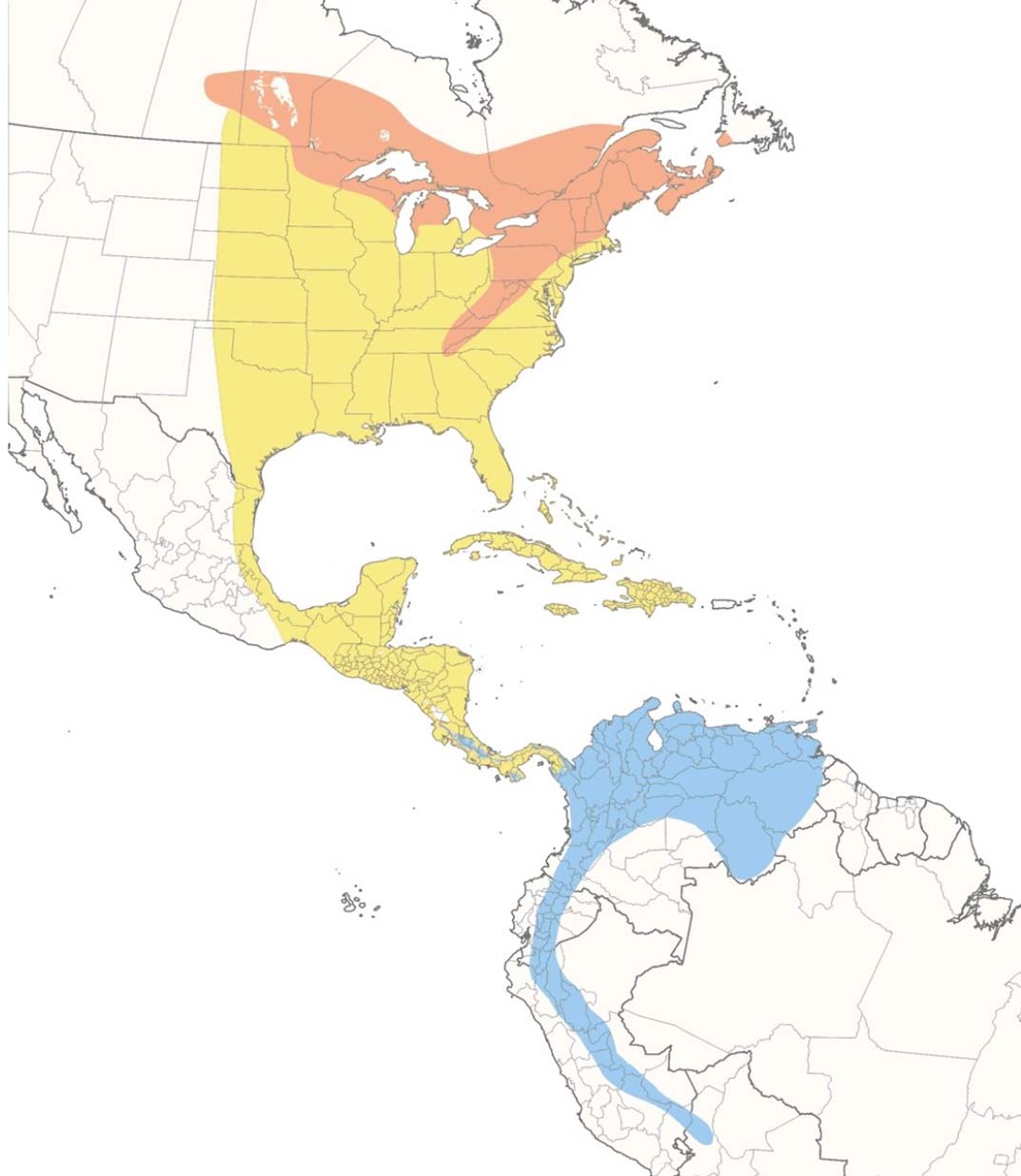

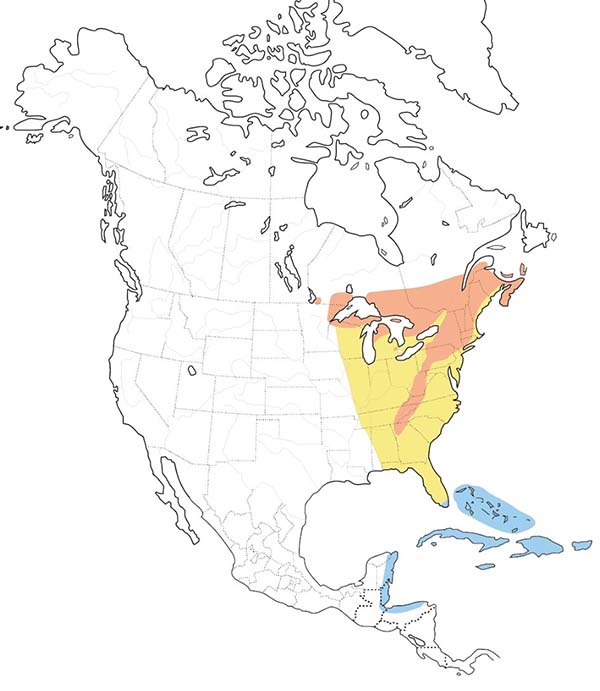

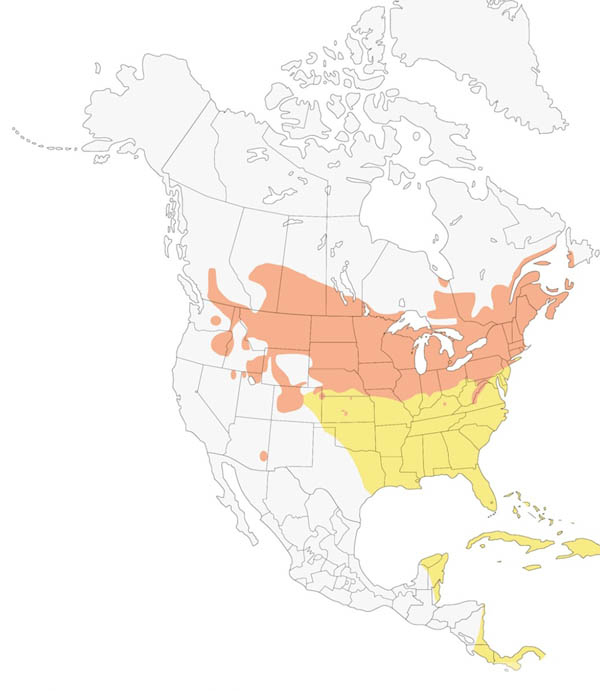

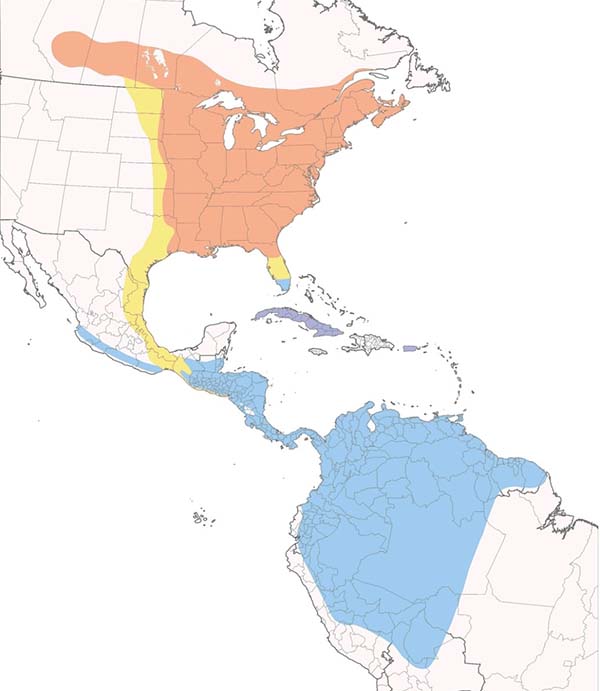

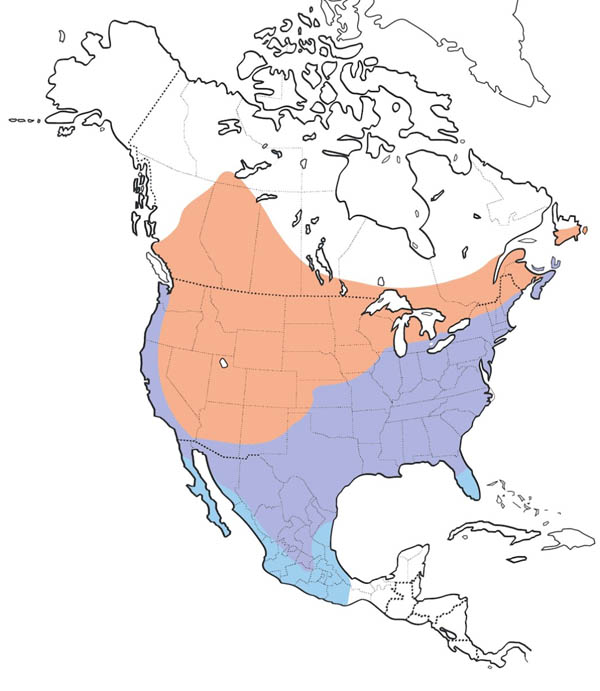

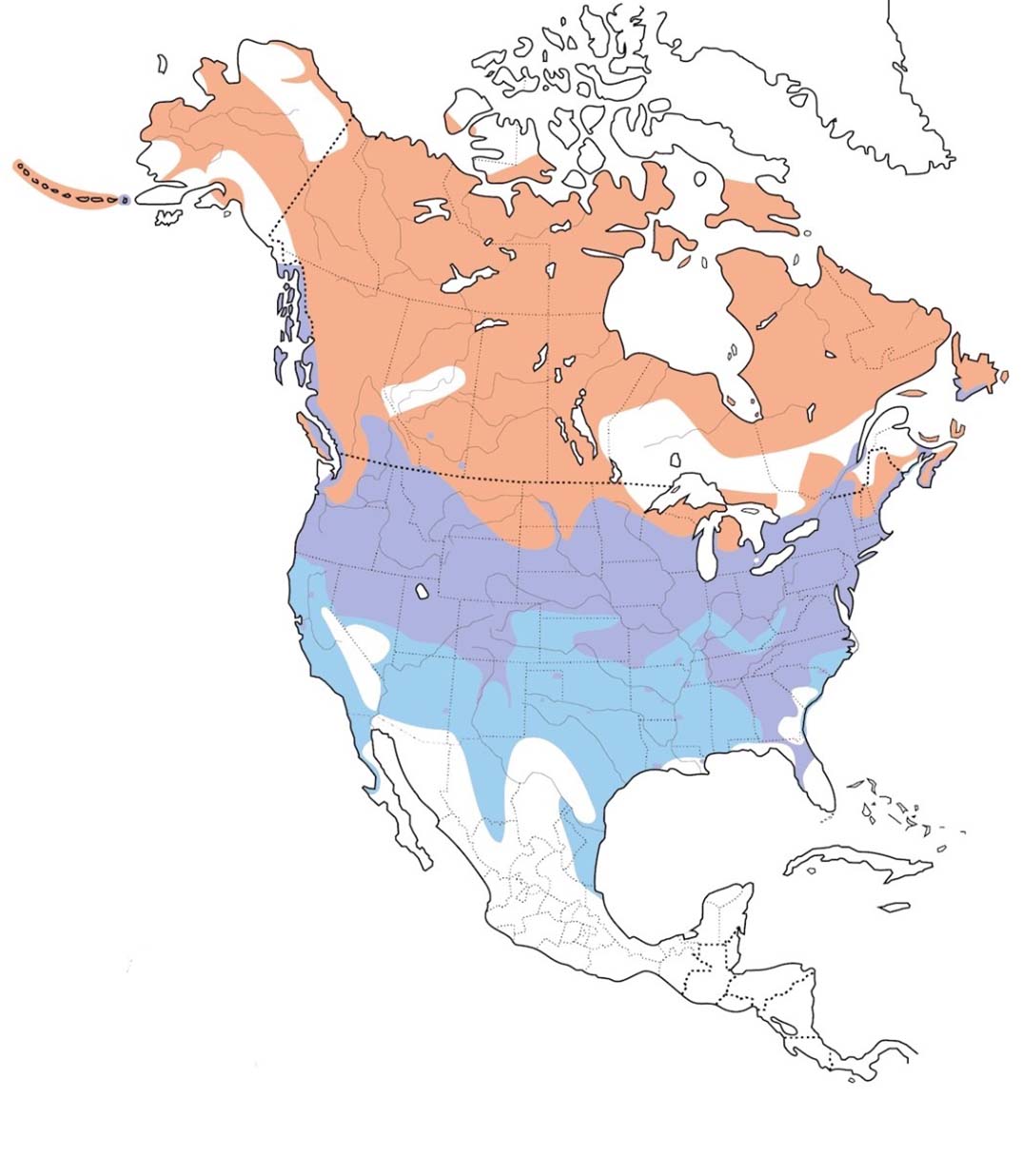

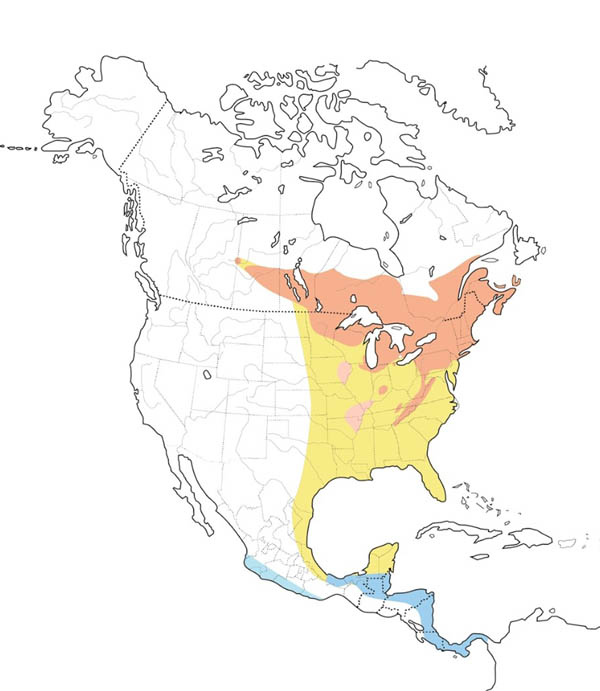

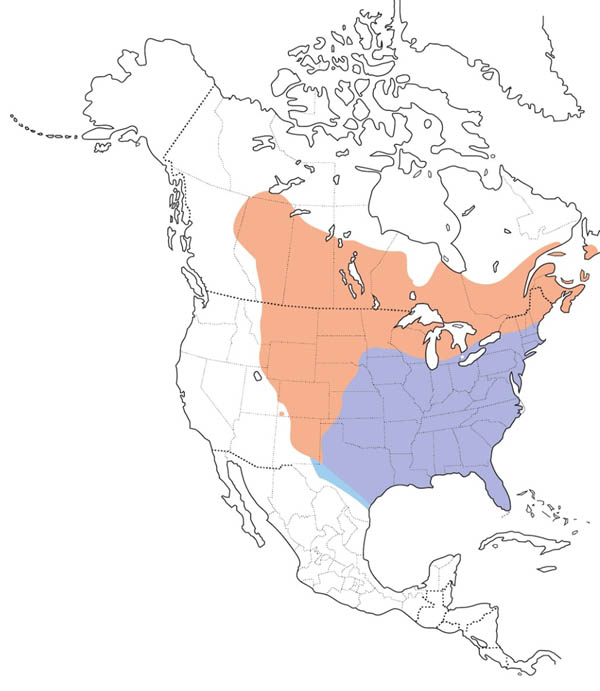

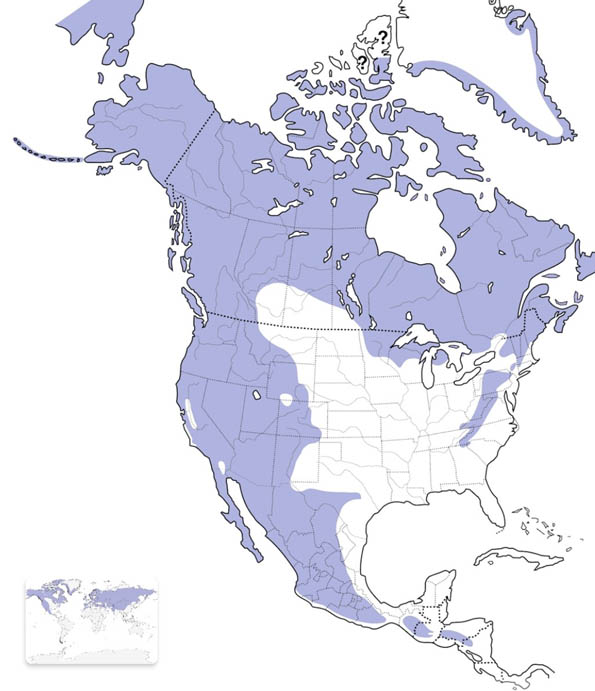

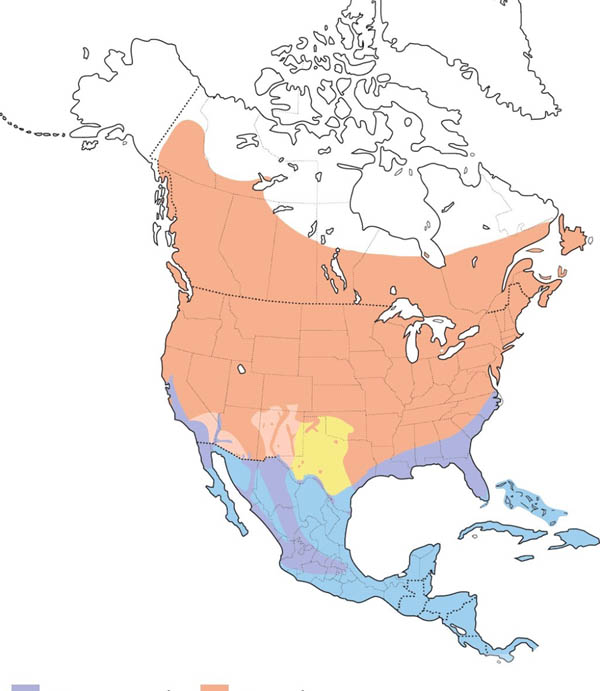

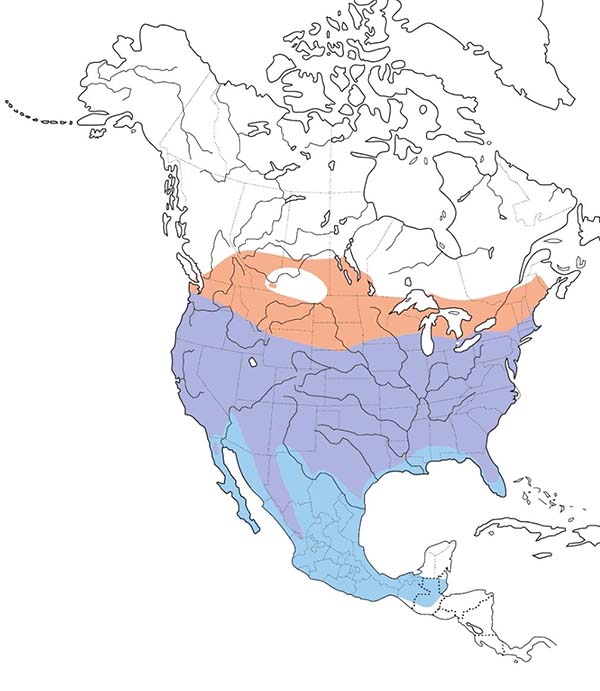

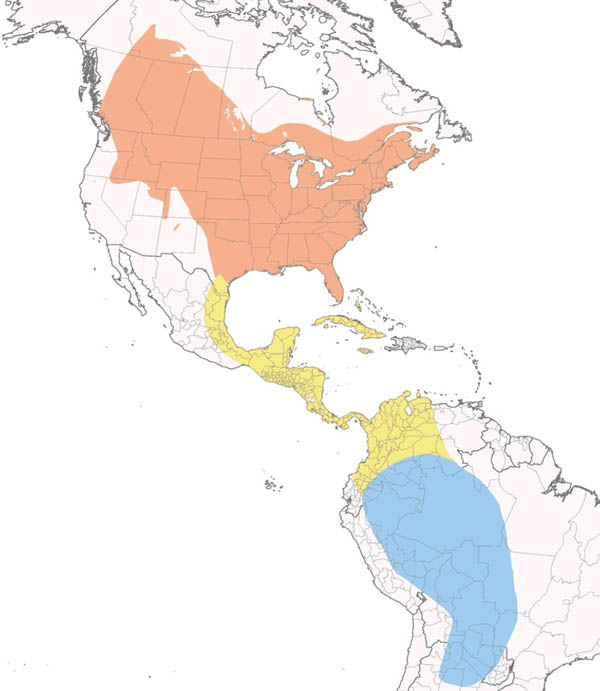

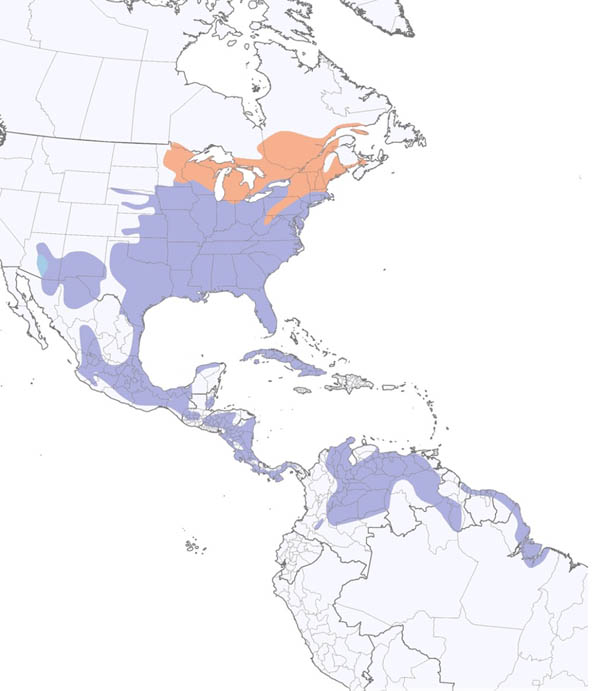

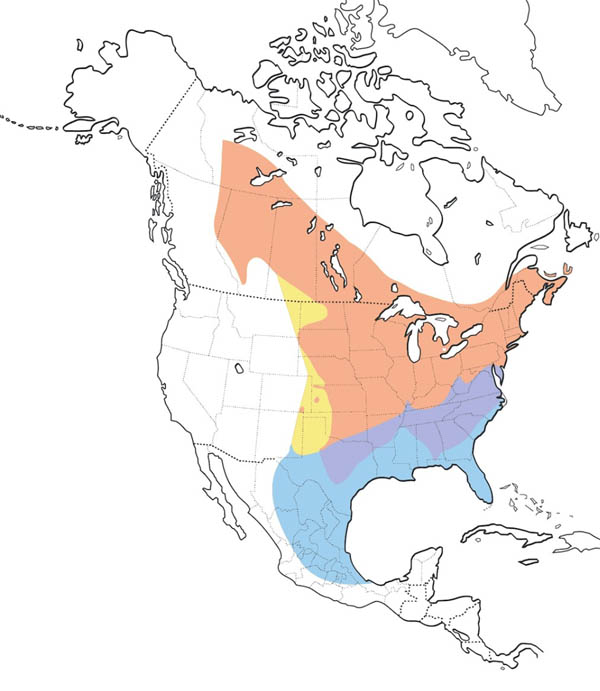

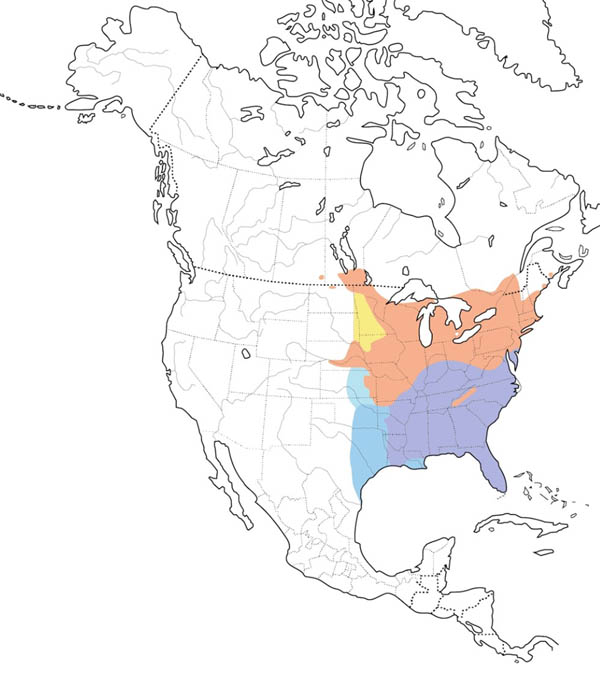

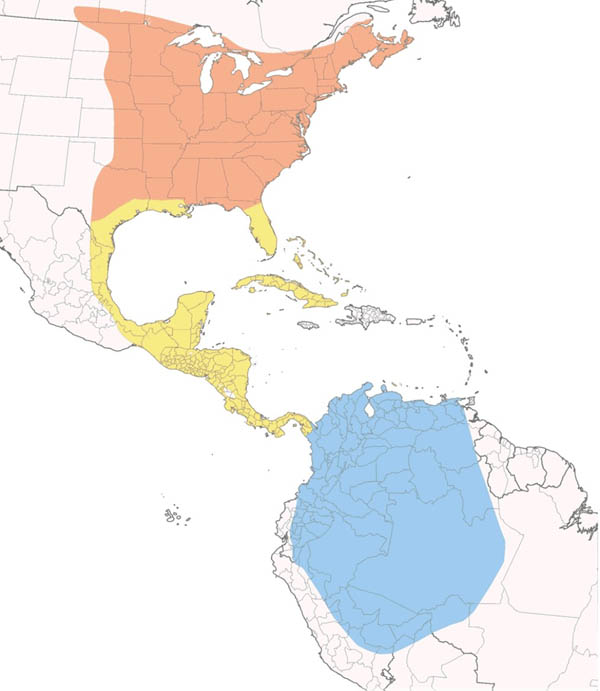

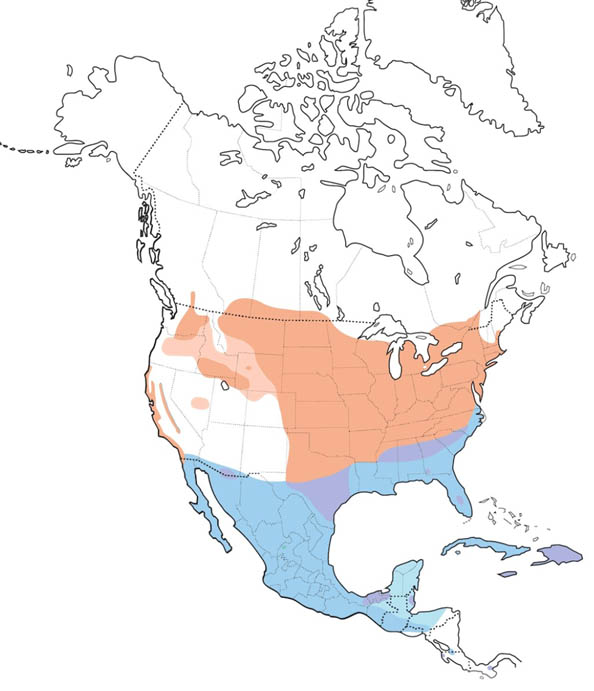

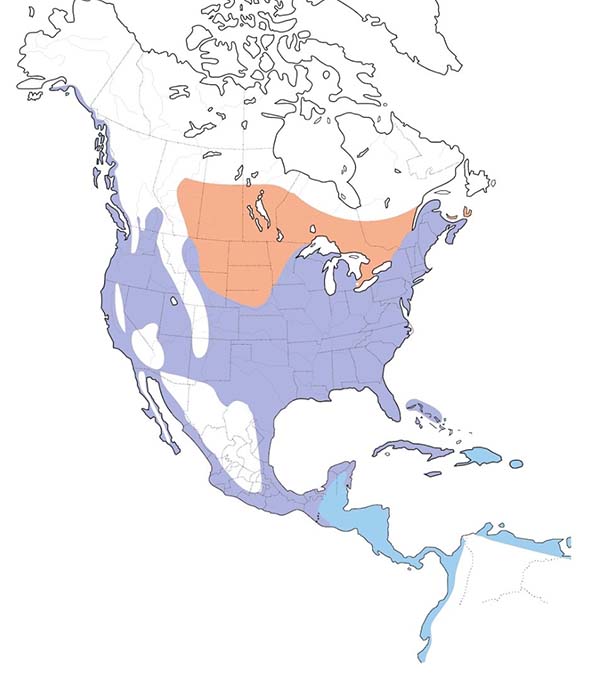

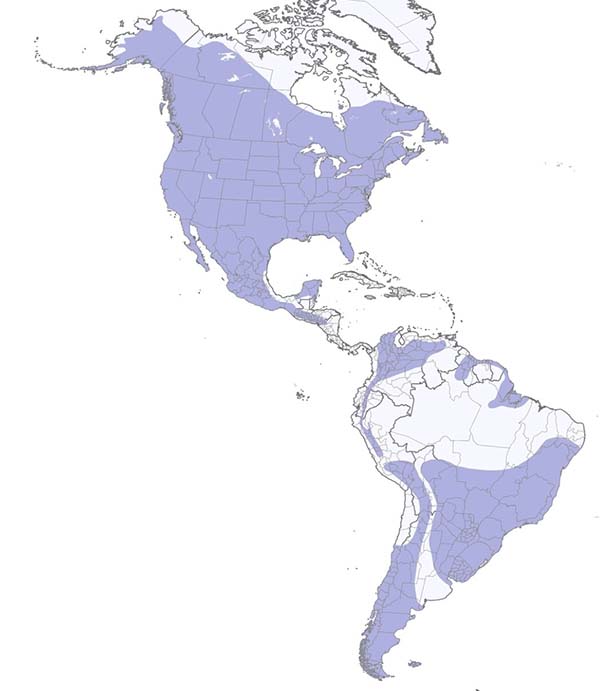

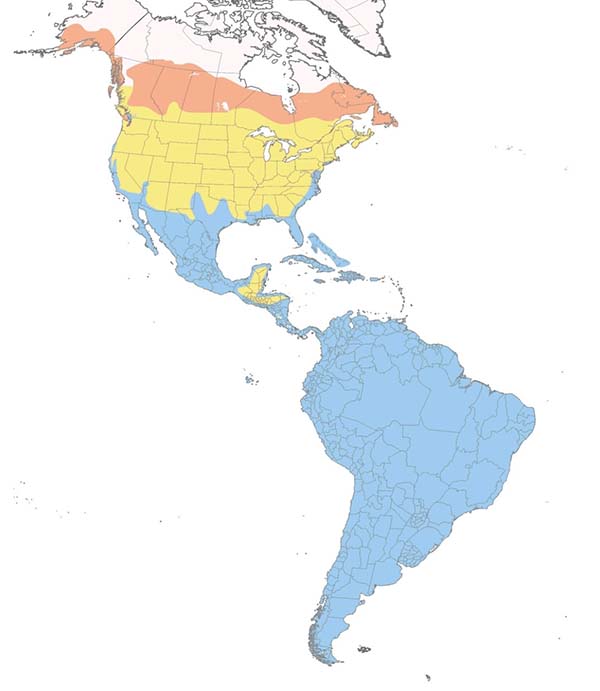

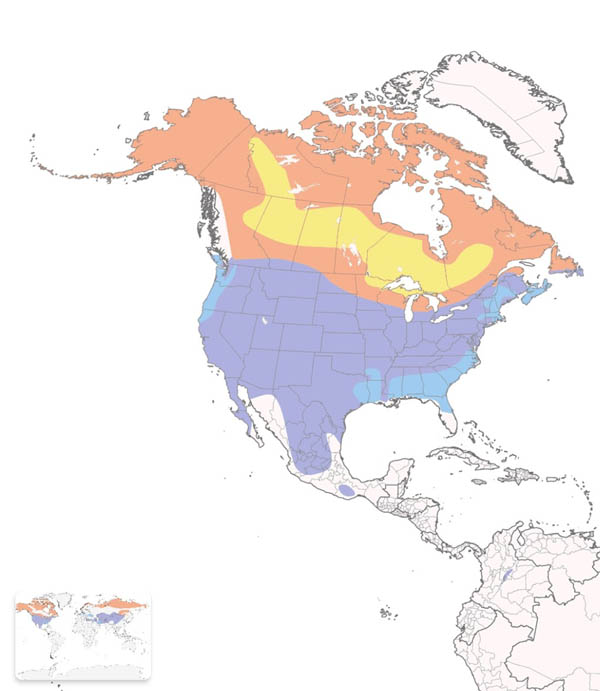

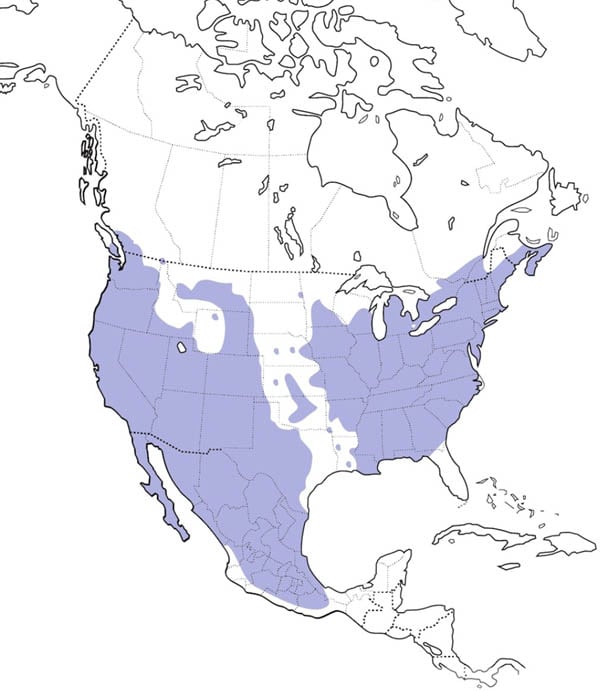

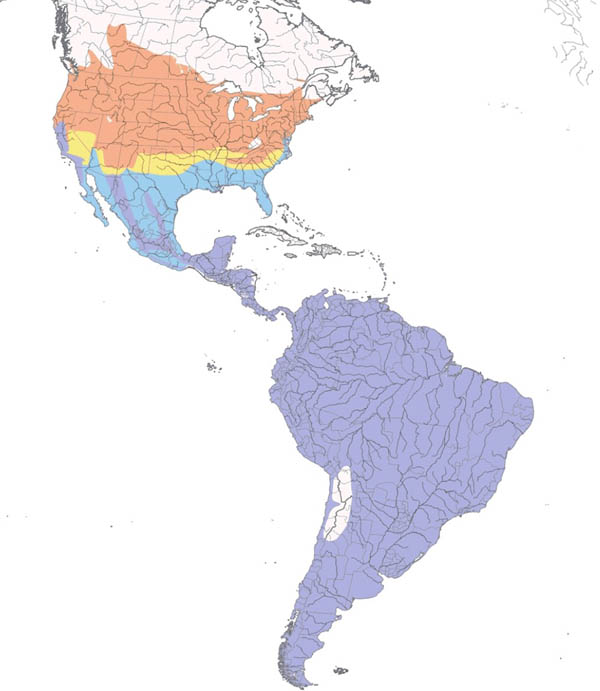

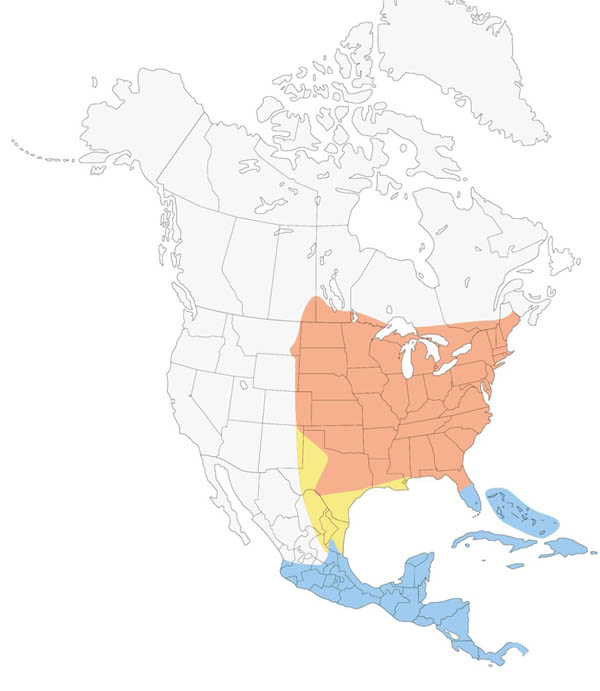

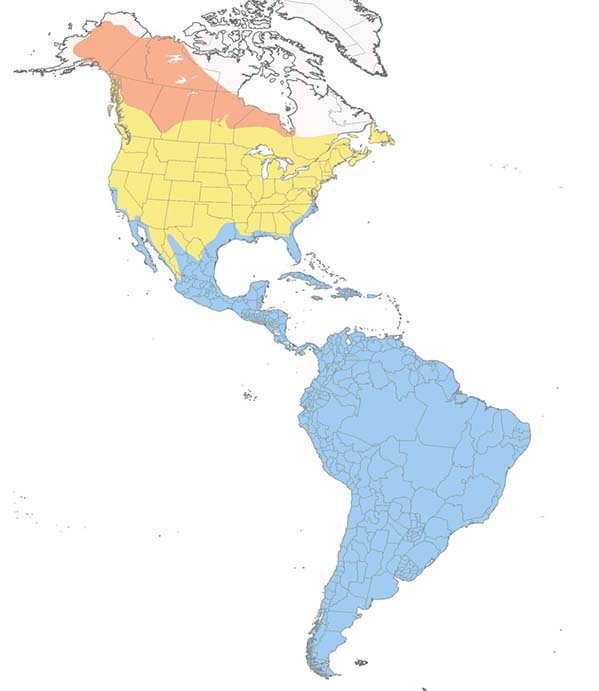

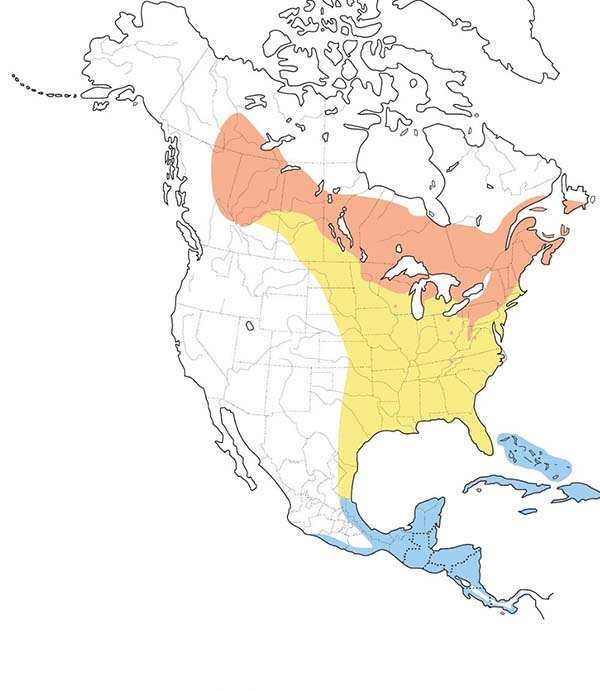

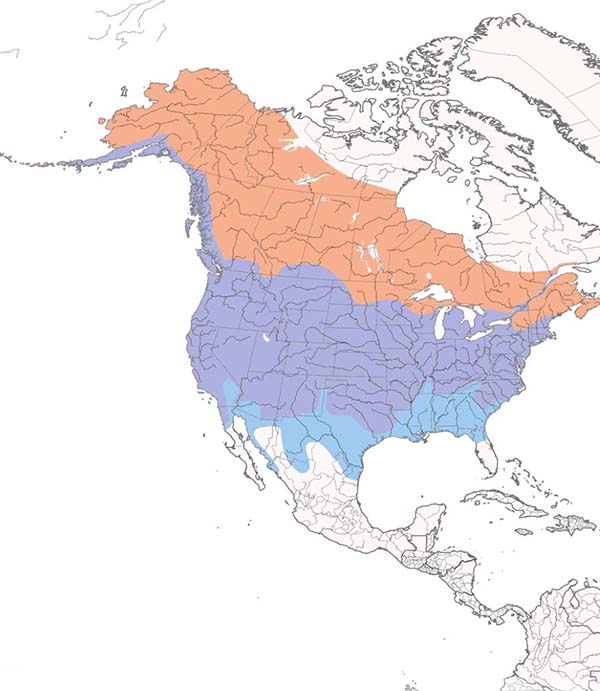

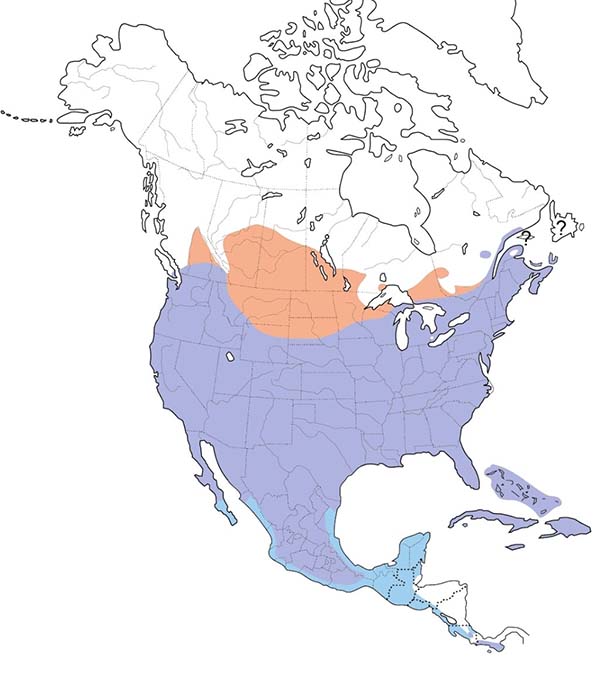

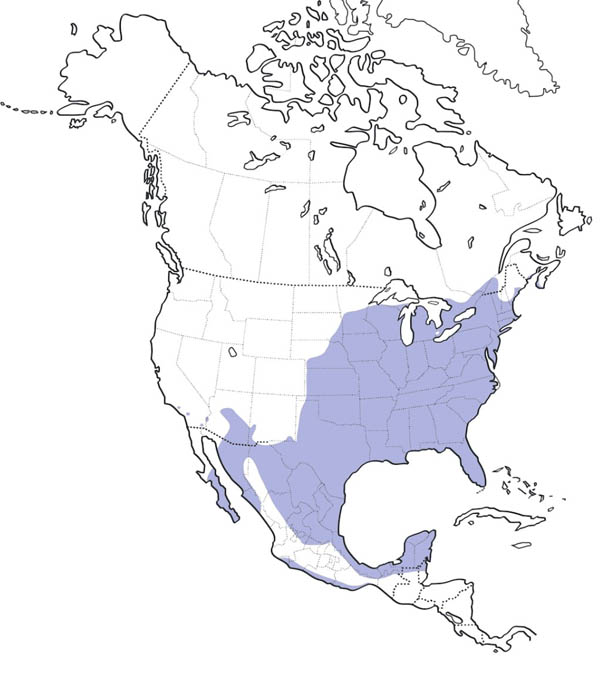

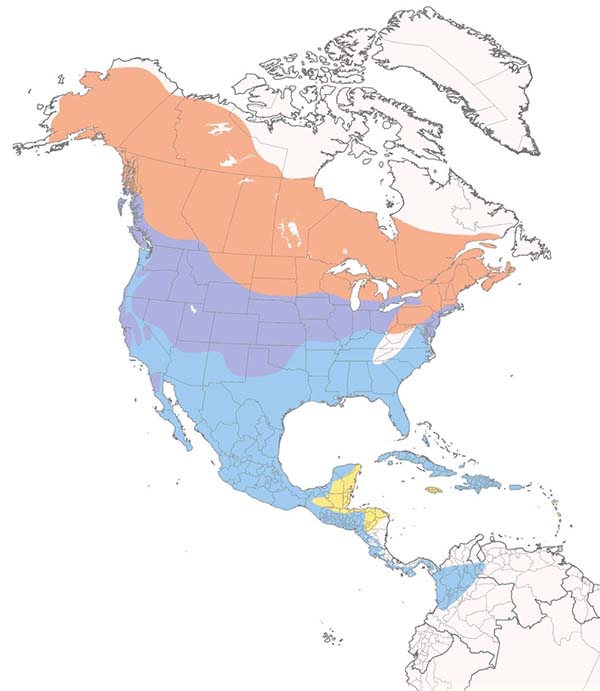

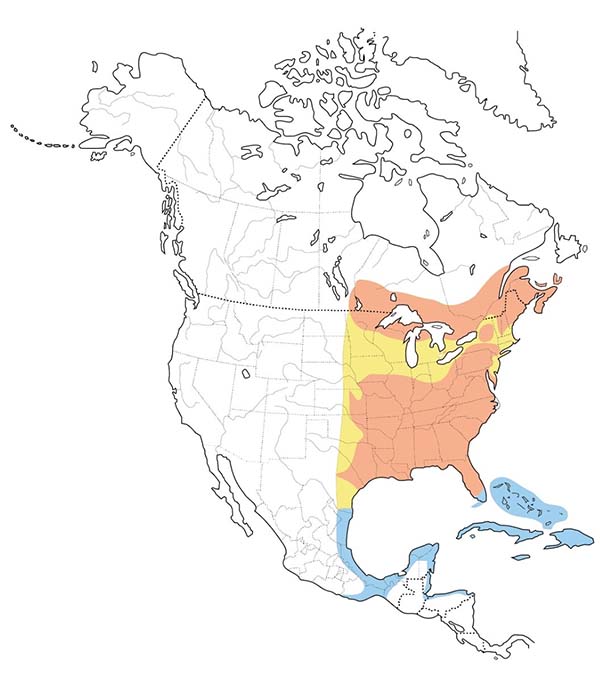

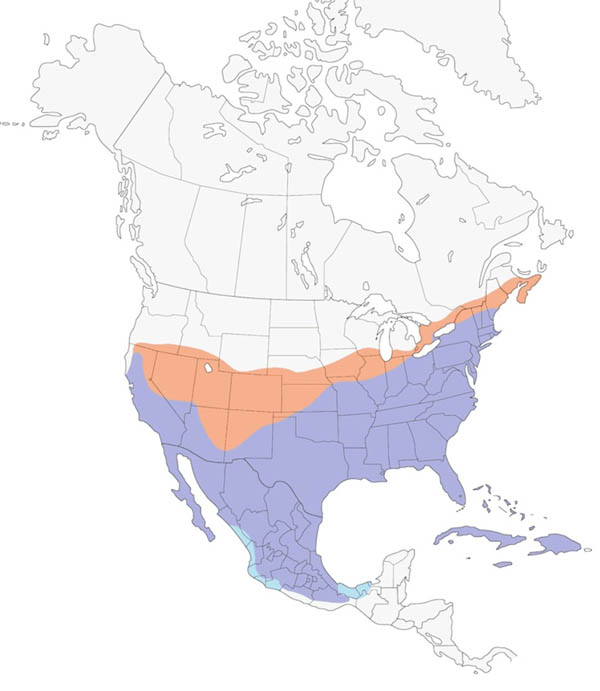

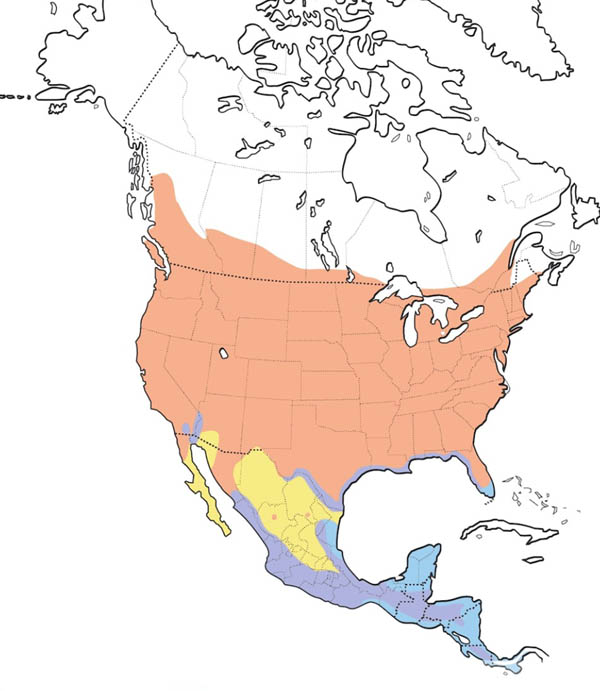

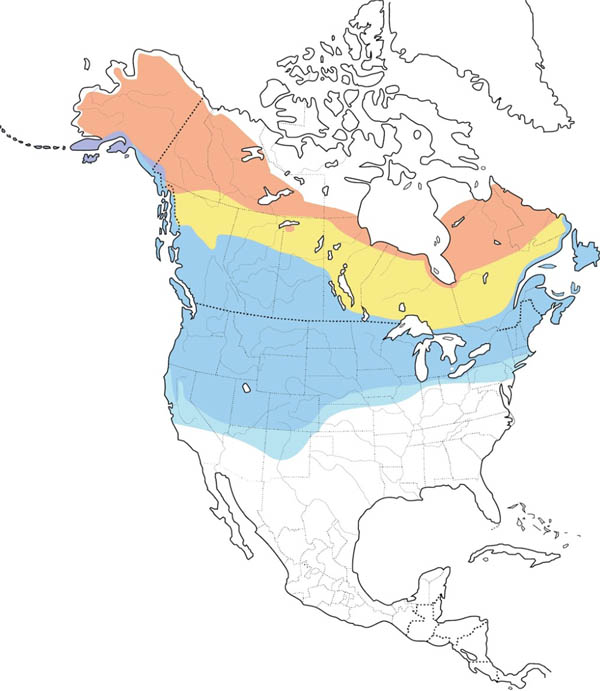

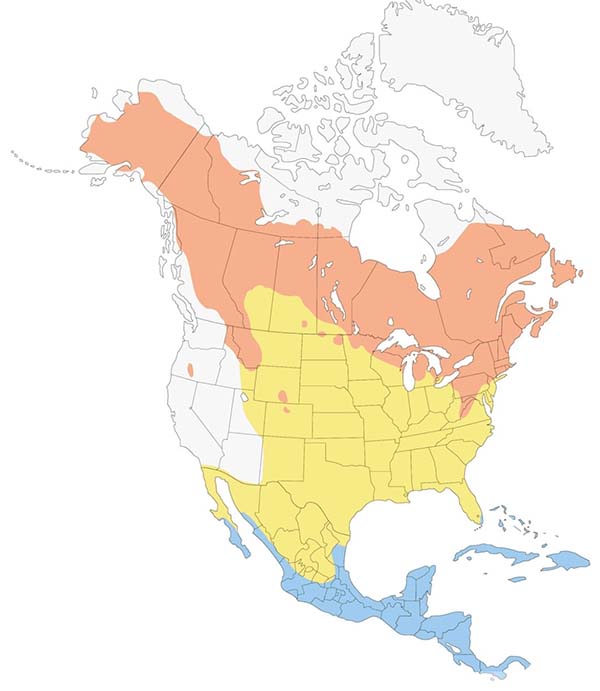

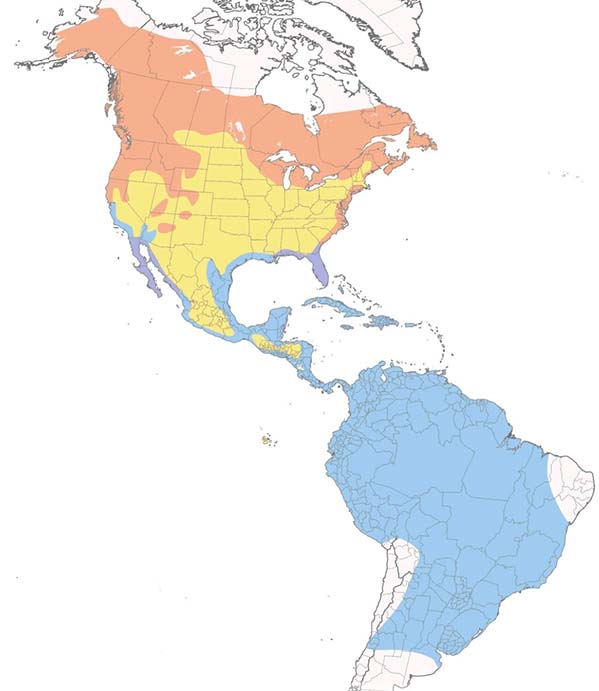

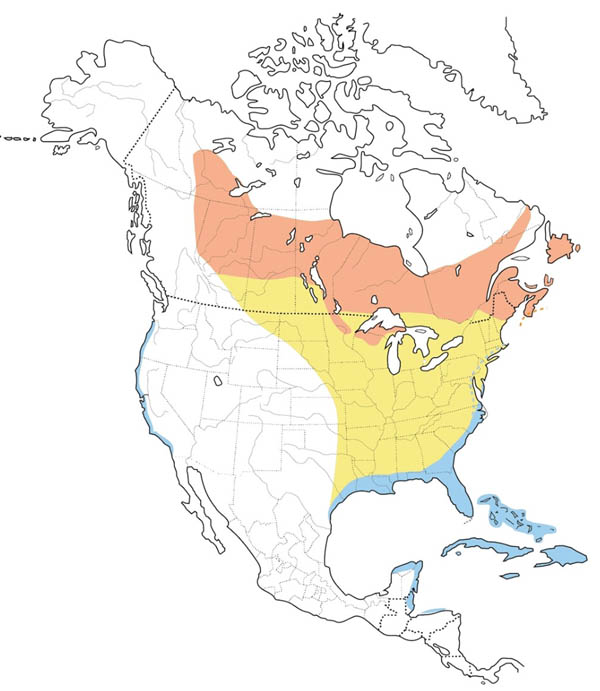

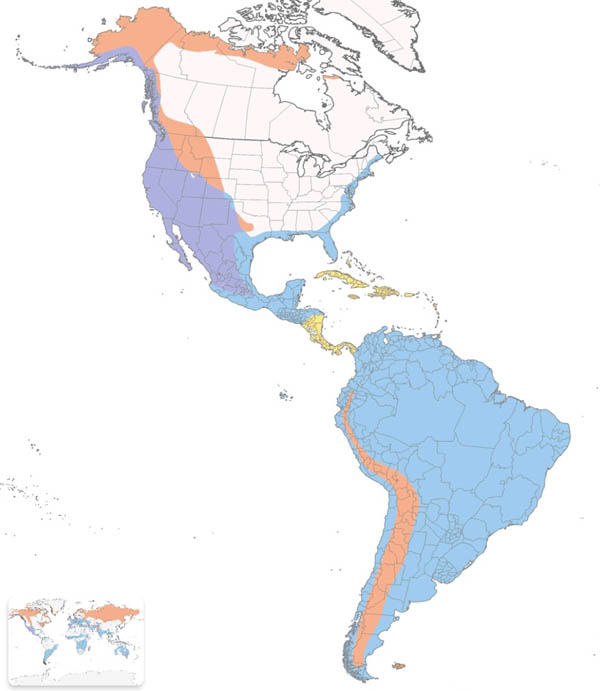

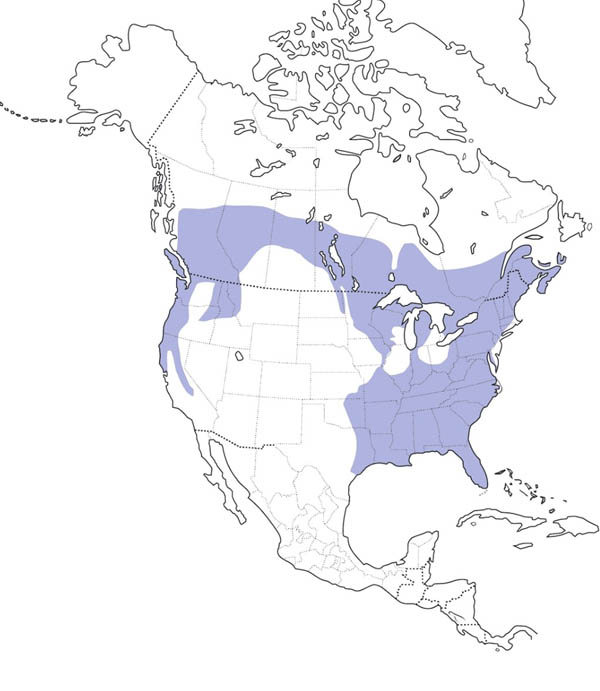

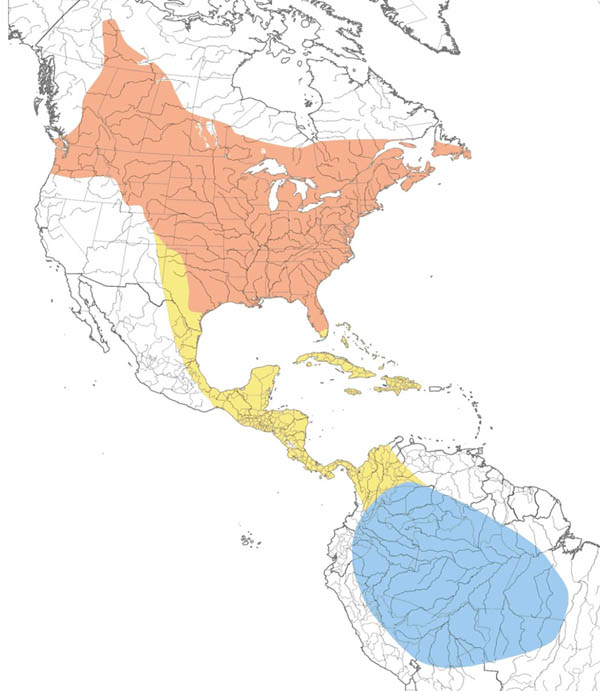

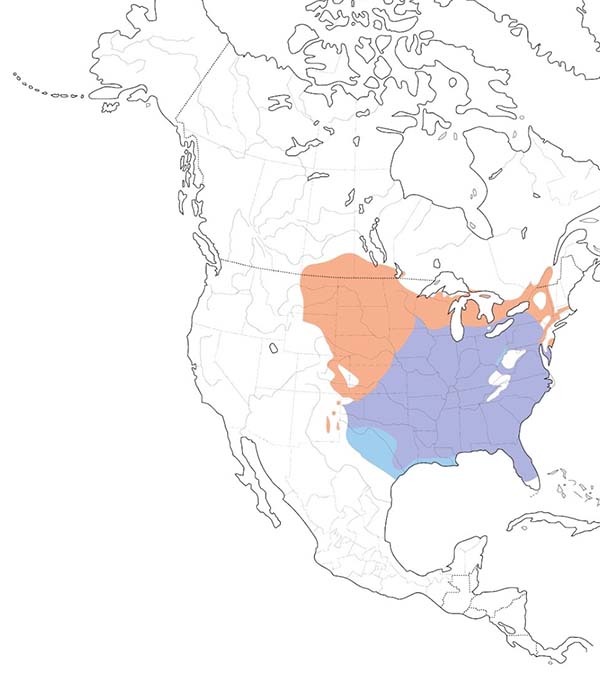

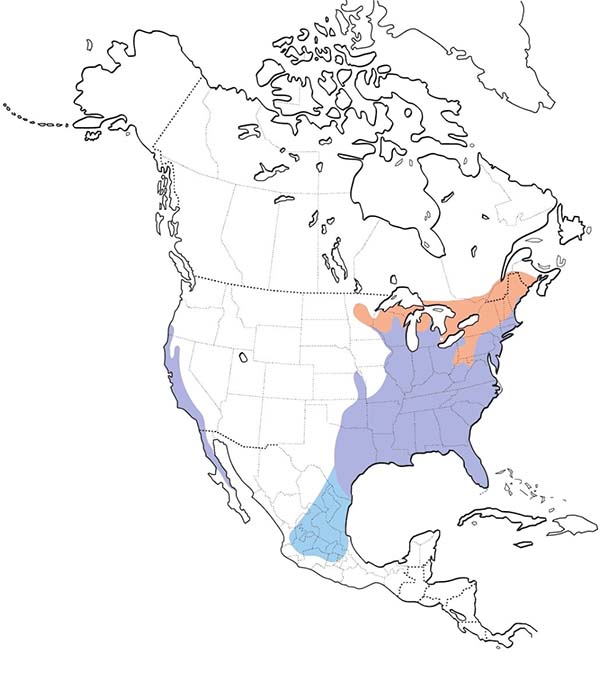

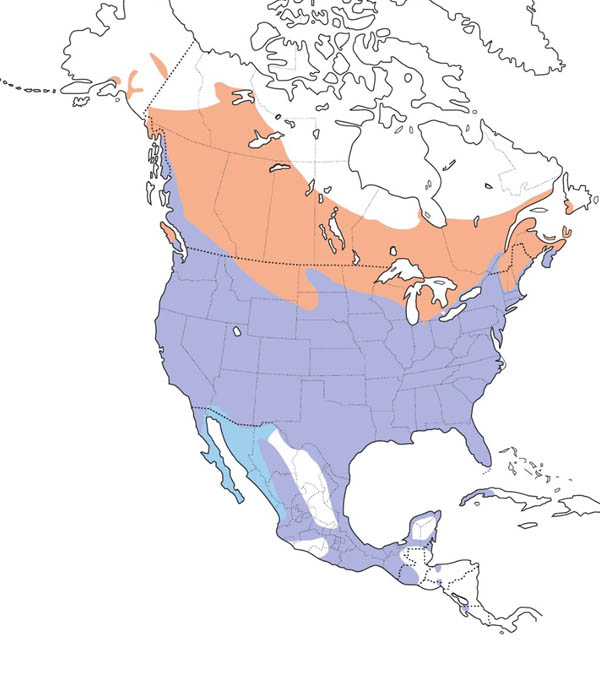

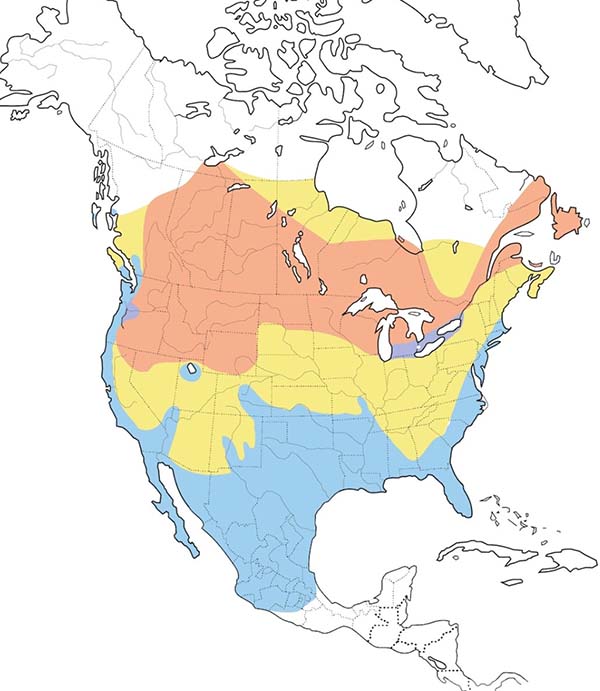

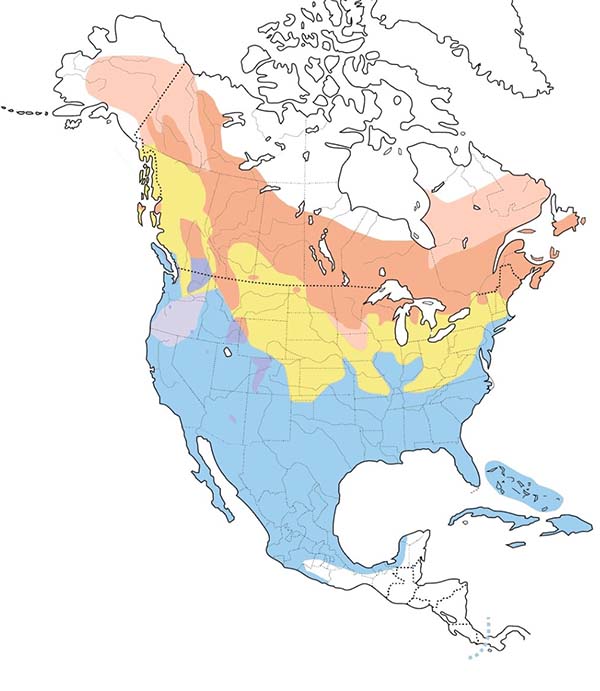

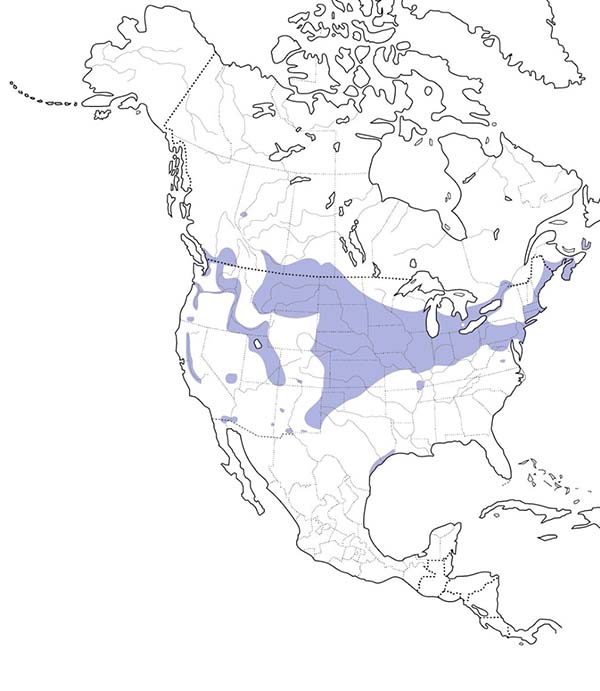

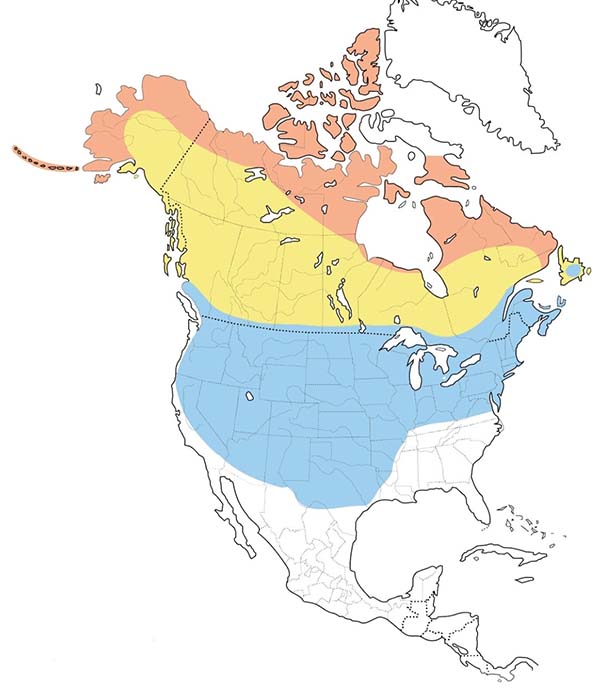

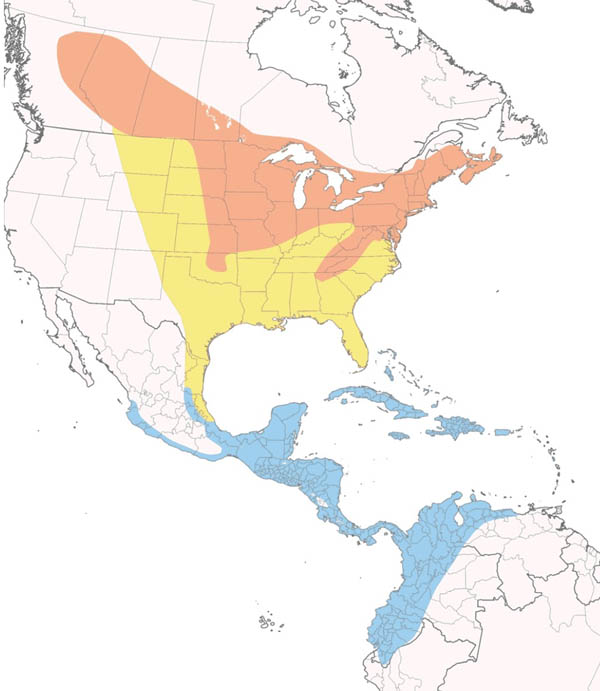

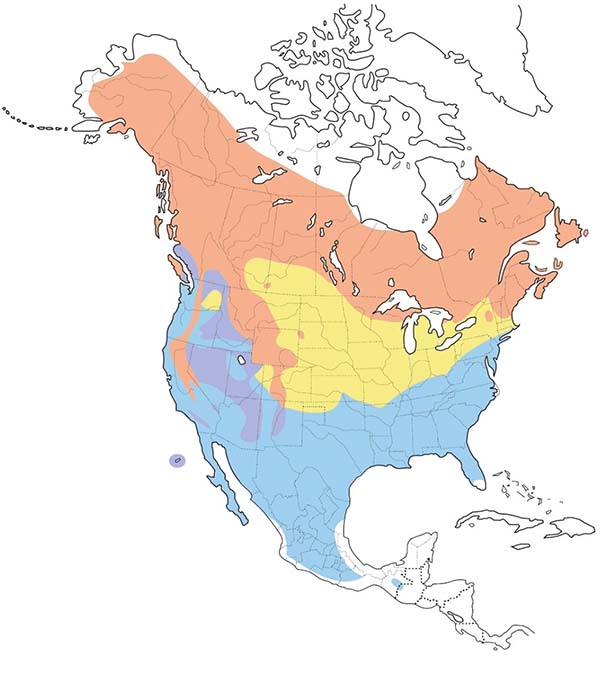

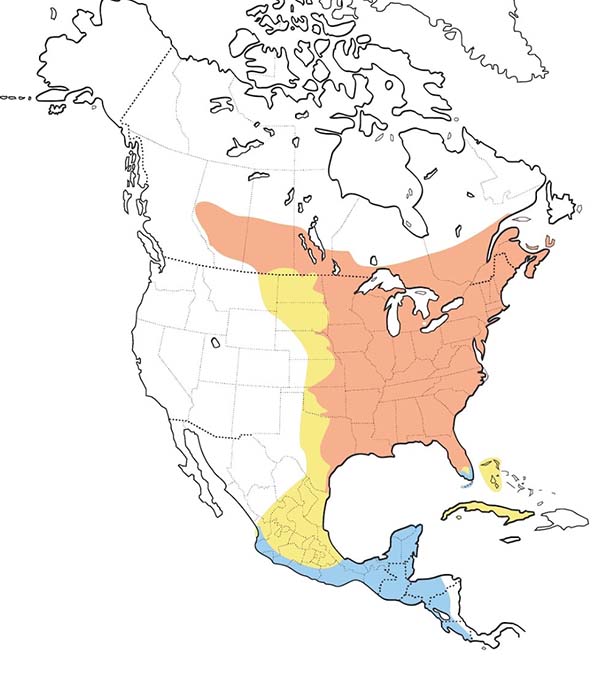

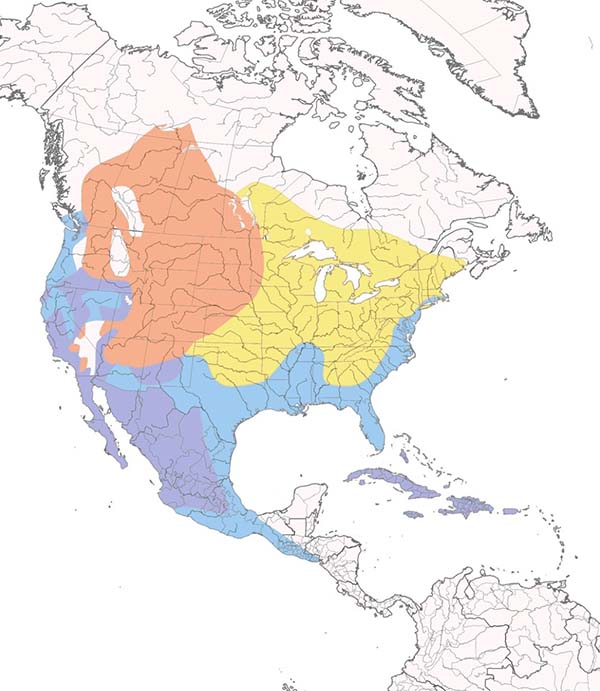

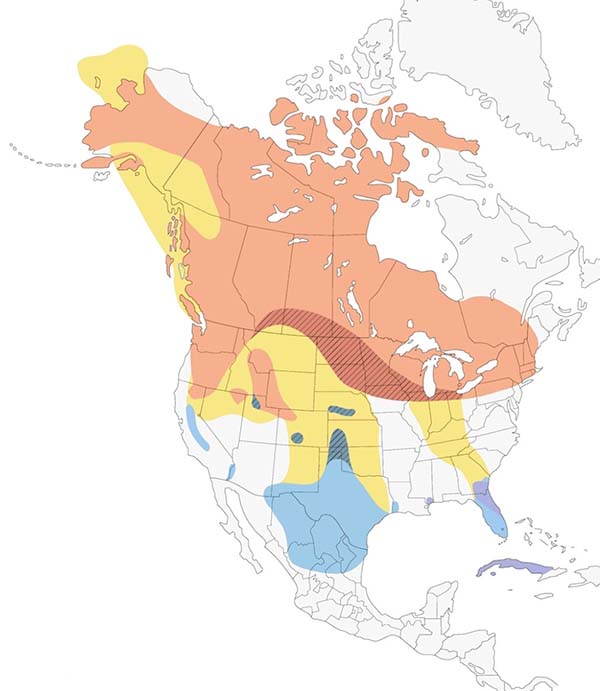

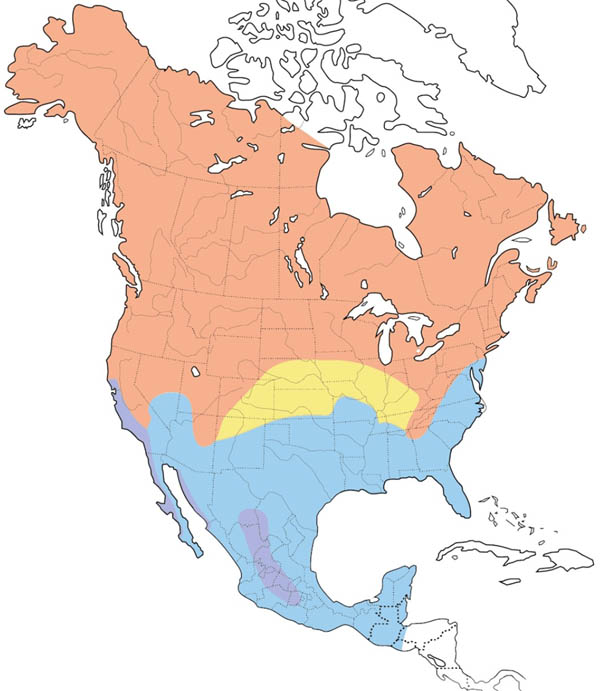

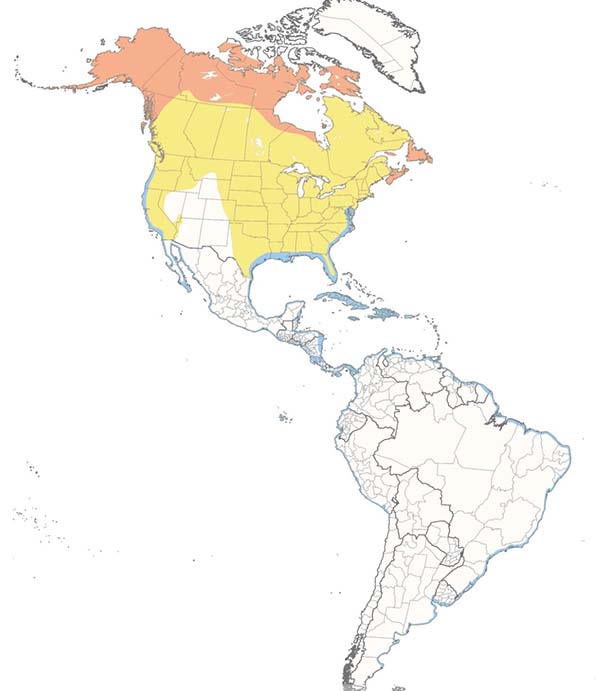

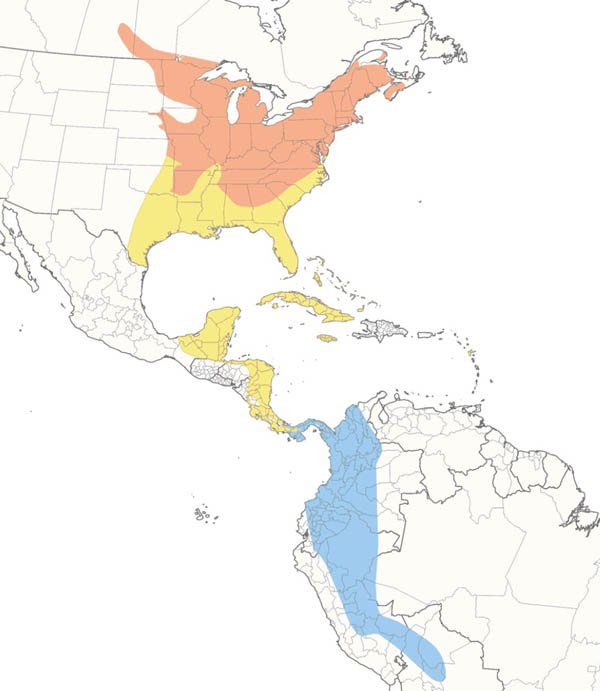

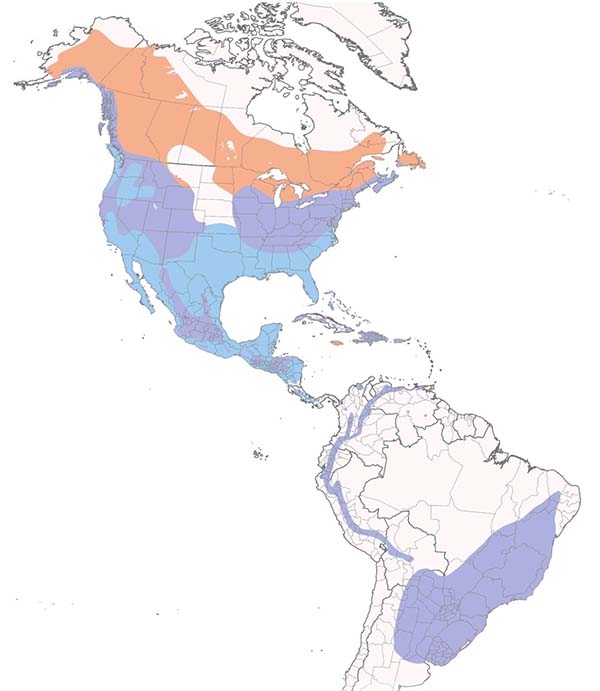

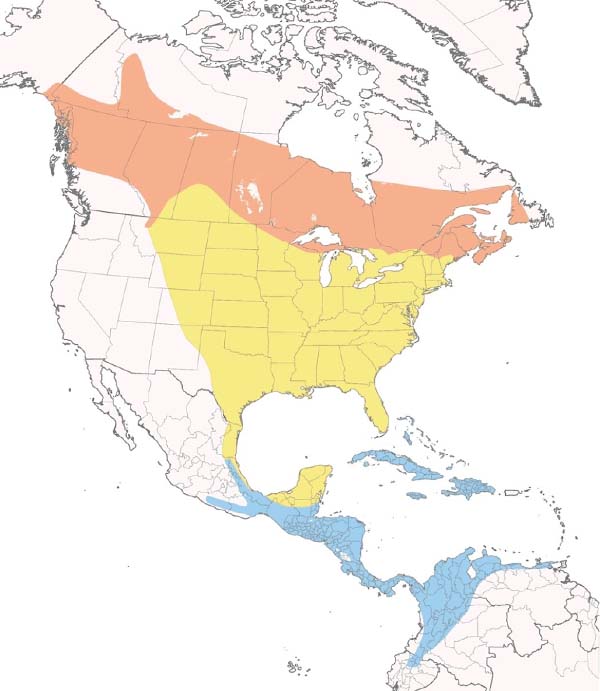

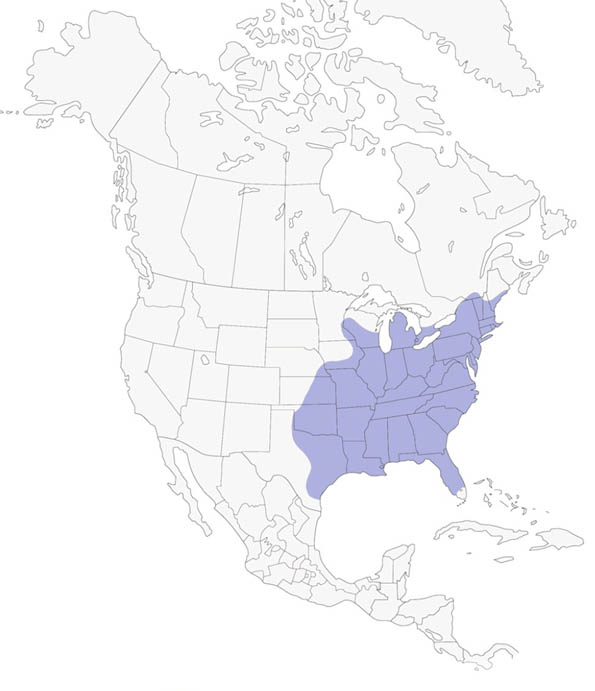

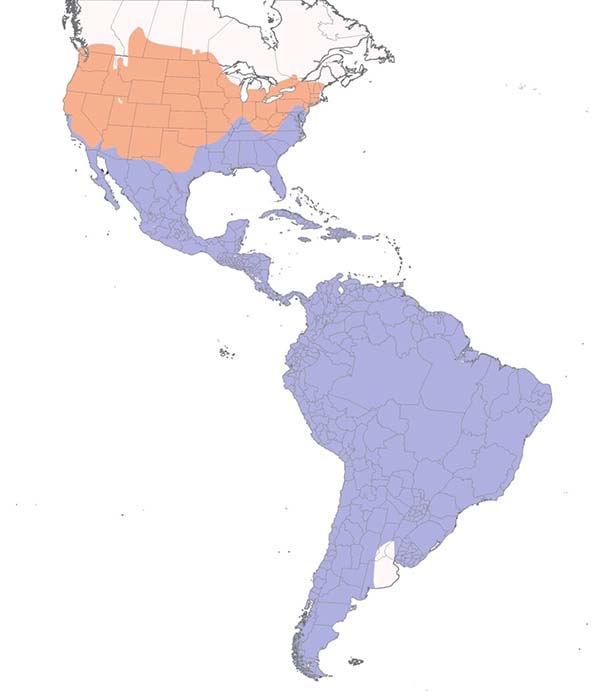

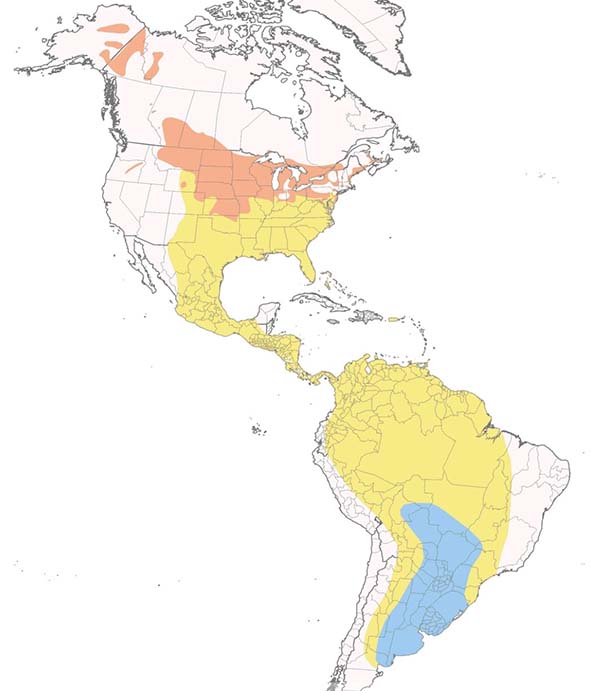

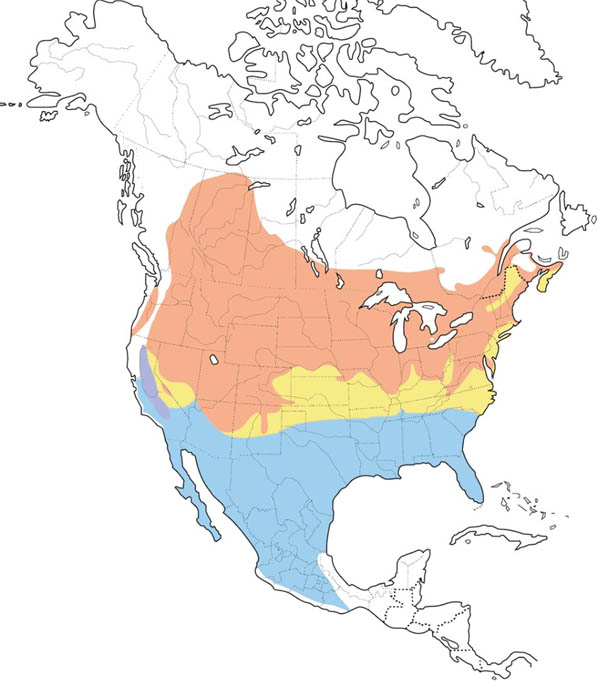

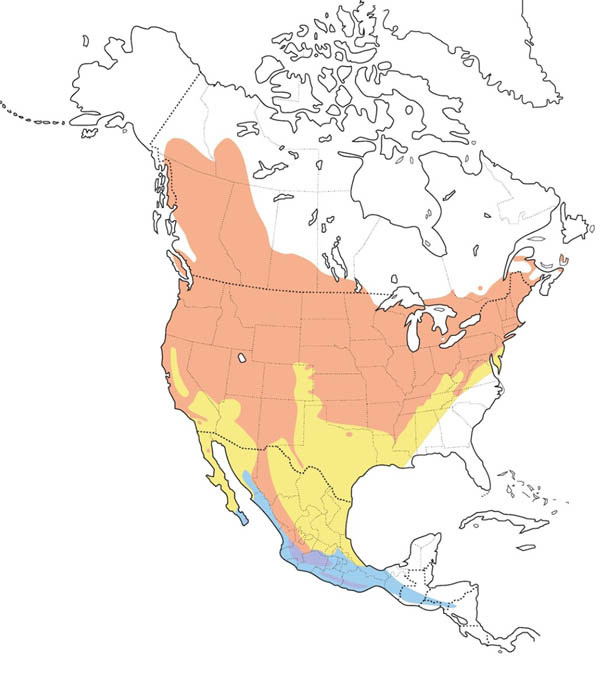

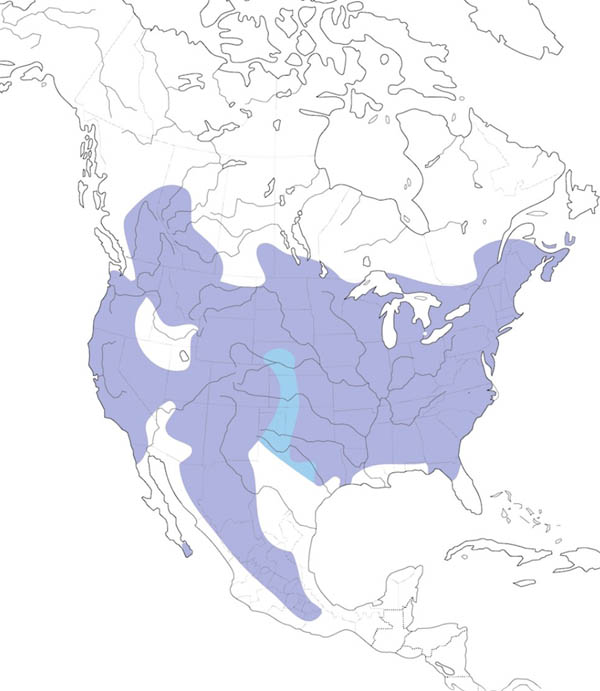

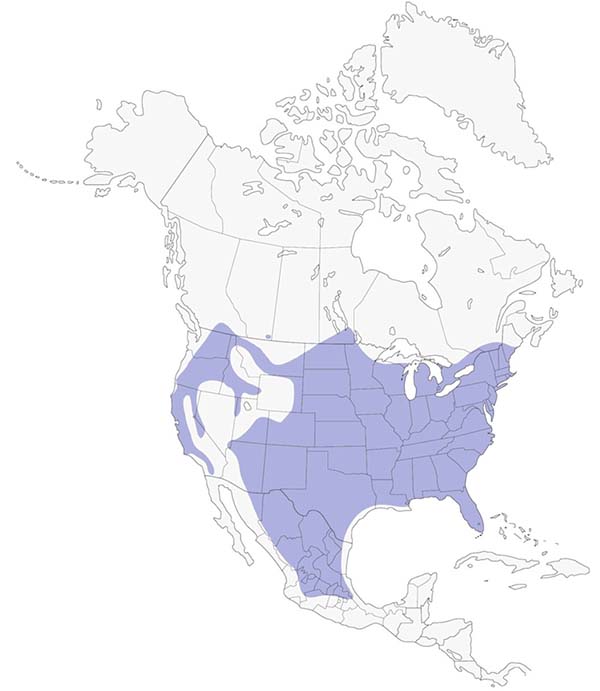

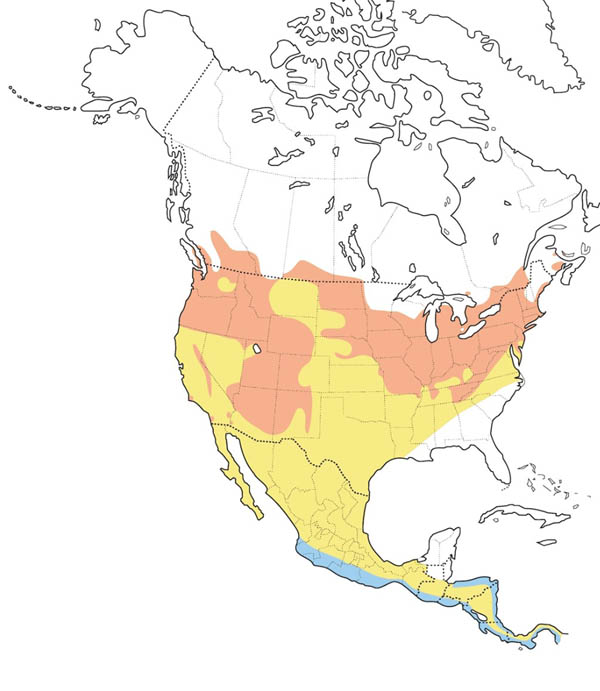

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Alder Flycatcher

Alder Flycatcher

Empidonax alnorum

A small bird that spends the summer catching flying insects in northern thickets. This bird and the Willow Flycatcher are so like each other that they were considered one species until the 1970s. The only differences apparent in the field are in their voices. However, voice is important to these birds: many other kinds of songbirds must learn their songs, but Willow and Alder flycatchers are born instinctively knowing the voice of their own species.

There are several subtle things we look at to differentiate between species, and foot color is one of them. Two species, Acadian and Yellow-bellied Flycatchers have purple-grayish legs whereas Alder/Willow and Least have black legs. This is a cool detail that you might not see using binoculars!

There are several subtle things we look at to differentiate between species, and foot color is one of them. Two species, Acadian and Yellow-bellied Flycatchers have purple-grayish legs whereas Alder/Willow and Least have black legs. This is a cool detail that you might not see using binoculars!

Sources:

- Alder Flycatcher. (2020, April 14). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/alder-flycatcher

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Kevin McGowan / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML41069641)

- Female: Dennis Forsythe / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML47212721)

- Juvenile: West Tennessee Historical Data / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML67545601)

- Nest/Eggs: Jim Lind / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML89952491)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about American Crow

American Crow

Corvus brachyrhynchos

Crows are thought to be among our most intelligent birds, and the success of the American Crow in adapting to civilization would seem to confirm this. Despite past attempts to exterminate them, crows are more common than ever in farmlands, towns, and even cities, and their distinctive caw is a familiar sound over much of the continent. Sociable, especially when not nesting, crows may gather in communal roosts on winter nights, sometimes with thousands or even tens of thousands roosting in one grove.

The largest crow found in North America, it has uniformly black plumage and a fan-shaped tail. Its bill is larger than other American crows but distinctly smaller than either raven. On rare occasions, individuals show white patches in wings. Juveniles have a brownish cast to feathers, a grayish eye, and grayish fleshy gape which quickly darkens after fledging. Crows fly steady, with low rowing wingbeats, and do not soar.

The largest crow found in North America, it has uniformly black plumage and a fan-shaped tail. Its bill is larger than other American crows but distinctly smaller than either raven. On rare occasions, individuals show white patches in wings. Juveniles have a brownish cast to feathers, a grayish eye, and grayish fleshy gape which quickly darkens after fledging. Crows fly steady, with low rowing wingbeats, and do not soar.

Sources:

- American Crow. (2020, September 23). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/american-crow

- American Crow: National Geographic. (2006). Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/birds/facts/american-crow

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Michael I Christie / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML267221661)

- Female: Shailesh Pinto / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML279256371)

- Juvenile: Michel Laquerre / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML262803421)

- Nest/Eggs: Burke Korol / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML89082241)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about American Goldfinch

American Goldfinch

Spinus tristis

A typical summer sight is a male American Goldfinch flying over a meadow, flashing golden in the sun, calling perchickory as it bounds up and down in flight. In winter, when males and females alike are colored in subtler brown, flocks of goldfinches congregate in weedy fields and at feeders, making musical and plaintive calls. In most regions this is a late nester, beginning to nest in mid-summer, perhaps to assure a peak supply of late-summer seeds for feeding its young.

The American Goldfinch only begins nesting from late July to September, when most other songbirds are winding down breeding activity. This timing coincides with the abundance of their chief food source — seeds — in the late summer months. Almost any sort of seed will do. Thistles are favored, but this goldfinch readily feeds on a wide variety of weed, flower, tree, and grass seeds, as well as buds, sap, berries, and, less commonly, insects.

This species has several adaptations suited to its granivorous (seed-eating) diet, including a strong, conical bill that easily gathers and splits seed, and dexterous legs and feet, which allow the American Goldfinch to easily scramble up and down plant stems and hang from seed heads while feeding, thereby accessing seed sources unavailable to other birds.

A male American Goldfinch in breeding plumage is easy to recognize: a bright, sunny yellow with jet-black wings and cap. Like other common feeder birds such as the Northern Cardinal or Dark-eyed Junco, the American Goldfinch is a sexually dimorphic species, with the female much drabber than the eye-catching male. In the goldfinch's case, this difference is especially apparent during the nesting season. In the winter, both sexes look much more alike, with feathers of brown, olive, and dull yellow-green, accented by buff or white markings. This noticeable change in the male's plumage leads some people to believe that American Goldfinches are absent in the winter, when in fact they may still be around — just in duller plumage! The males' molt from drab to brilliant in the spring makes it seem as if they just appeared from nowhere.

The American Goldfinch only begins nesting from late July to September, when most other songbirds are winding down breeding activity. This timing coincides with the abundance of their chief food source — seeds — in the late summer months. Almost any sort of seed will do. Thistles are favored, but this goldfinch readily feeds on a wide variety of weed, flower, tree, and grass seeds, as well as buds, sap, berries, and, less commonly, insects.

This species has several adaptations suited to its granivorous (seed-eating) diet, including a strong, conical bill that easily gathers and splits seed, and dexterous legs and feet, which allow the American Goldfinch to easily scramble up and down plant stems and hang from seed heads while feeding, thereby accessing seed sources unavailable to other birds.

A male American Goldfinch in breeding plumage is easy to recognize: a bright, sunny yellow with jet-black wings and cap. Like other common feeder birds such as the Northern Cardinal or Dark-eyed Junco, the American Goldfinch is a sexually dimorphic species, with the female much drabber than the eye-catching male. In the goldfinch's case, this difference is especially apparent during the nesting season. In the winter, both sexes look much more alike, with feathers of brown, olive, and dull yellow-green, accented by buff or white markings. This noticeable change in the male's plumage leads some people to believe that American Goldfinches are absent in the winter, when in fact they may still be around — just in duller plumage! The males' molt from drab to brilliant in the spring makes it seem as if they just appeared from nowhere.

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020e, July 20). American Goldfinch. https://abcbirds.org/bird/american-goldfinch/

- American goldfinch. (2020, April 14). Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/american-goldfinch

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Tyler Ekholm / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML276709491)

- Female: Jim St Laurent / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML273270501)

- Juvenile: Jennifer Coffey / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML269184471)

- Nest/Eggs: Janet Getgood / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML156263381)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about American Kestrel

American Kestrel

Turdus migratorius

About the size of a Blue Jay, the American Kestrel is the smallest falcon in North America. Common nicknames for this scrappy little raptor include "sparrow hawk" (after the distantly related Eurasian Sparrowhawk), "grasshopper hawk," for one of its favorite prey items, and "killy hawk," due to its shrill call. The American Kestrel is found in the same open habitat as birds including the Eastern Meadowlark and Barn Swallow.

American Kestrels have two black spots, known as ocelli ("little eyes" in Latin), at the back of their heads. These false "eyes" help protect this little falcon from potential attackers sneaking up from the rear, whether they are predators or mobbing songbirds. American Kestrels also have two vertical black facial markings on each side of the head, in contrast to most other falcon species, which only have one.

It is fairly easily to identify an American Kestrel by its fast flight and habit of pumping its tail up and down while perched. This bird is also quite vocal, sounding off with a loud, repeated "killy, killy, killy" when excited or alarmed.

American Kestrels have two black spots, known as ocelli ("little eyes" in Latin), at the back of their heads. These false "eyes" help protect this little falcon from potential attackers sneaking up from the rear, whether they are predators or mobbing songbirds. American Kestrels also have two vertical black facial markings on each side of the head, in contrast to most other falcon species, which only have one.

It is fairly easily to identify an American Kestrel by its fast flight and habit of pumping its tail up and down while perched. This bird is also quite vocal, sounding off with a loud, repeated "killy, killy, killy" when excited or alarmed.

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020e, July 20). American Kestrel. https://abcbirds.org/bird/american-kestrel/

- Maryland birds: American Kestrel. (n.d.). Retrieved May 10, 2021, from https://dnr.maryland.gov/wildlife/Pages/plants_wildlife/American_Kestrel.aspx

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Ana Paula Oxom / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML278754201)

- Female: barbara taylor / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML269554061)

- Juvenile: Dana Kornitz / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML262589361)

- Nest/Eggs: Aaron Souder / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML241389601)

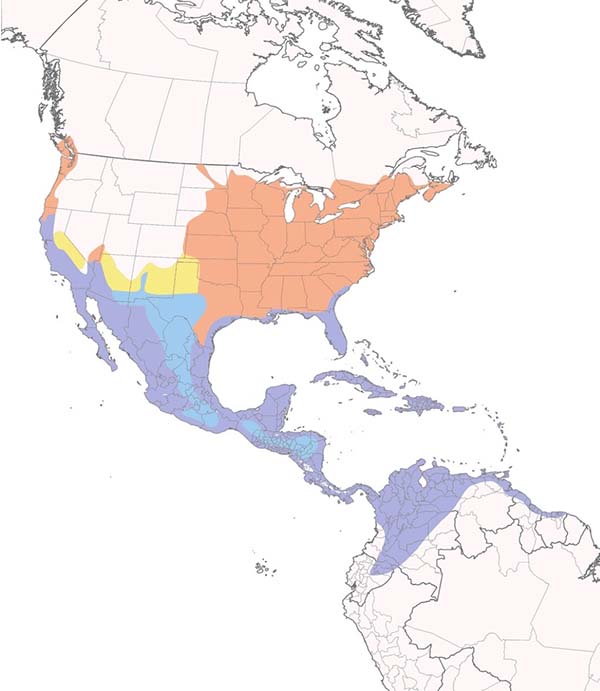

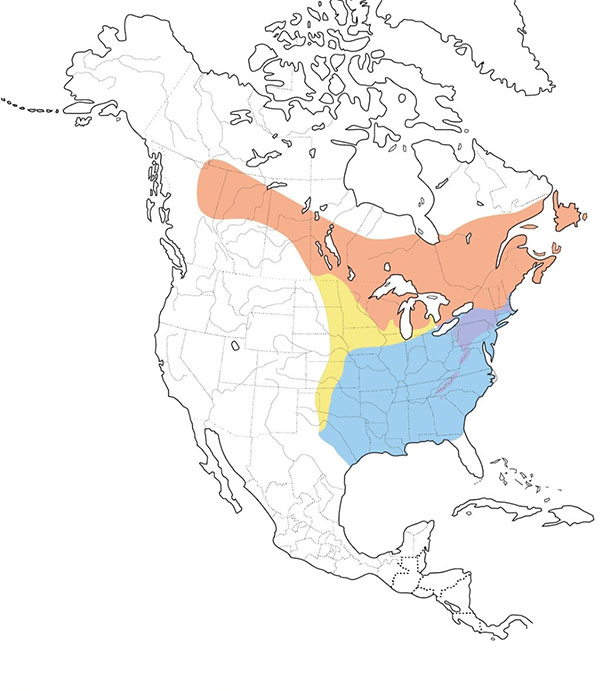

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about American Redstart

American Redstart

Setophaga ruticilla

One of our most recognizable wood warblers, the eye-catching American Redstart is named for the male's vivid reddish-orange tail patches; "start" is an old English word for tail. In Latin America, this redstart is often called candelita, or "little torch." American Redstarts winter in Central America, northern South America, and the Caribbean, including the island of Hispaniola.

American Redstarts are active feeders, taking insects by flycatching or gleaning from foliage. Redstarts are often observed quickly fanning their tails open and closed; this "flashing" of the orange or yellow patches on the birds' tails startles their prey out of hiding.

Male American Redstarts have a somewhat unusual molt strategy, at least for North American wood warblers. By the end of breeding season, most warblers that are sexually dimorphic (males and females have different plumage) are relatively easy to sex because they look different. Redstarts, however, are different: young males remain in brown and yellow plumage, looking very much like females, until after their first breeding season, at which point they replace all the feathers on their body and become black and orange. Birds molt at least once each year, and in the case of redstarts, once a male has molted into its black and orange plumage, it will grow new black, and orange feathers every time it molts for the rest of its life!

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020a, June 24). American Redstart. https://abcbirds.org/bird/american-redstart/

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Tyler Ekholm / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML276709491)

- Female: Jim St Laurent / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML273270501)

- Juvenile: Jennifer Coffey / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML269184471)

- Nest/Eggs: Janet Getgood / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about American Robin

American Robin

Turdus migratorius

The American Robin is one of North America's most widespread, familiar, and well-loved songbirds. Although homesick settlers named it after the European Robin because of its reddish-orange breast, the two species are not closely related. The American Robin is a thrush, related to the Wood Thrush, Swainson's Thrush, and Hermit Thrush, while the European Robin is an Old World flycatcher.

In late winter, male American Robins begin to sing their cheerful, caroling song (cheerily cheer-up cheerio.), a sure harbinger of springtime for many. The early chorus continues through spring, into summer. It is one of the first birds to sing in the morning, often beginning well before dawn, and one of the last to be heard at night. In addition, this species has a variety of distinctive calls, including a shrill cheep alarm call and a low tuktuktuk when disturbed.

Robins are large with dark gray-brown backs and wings, gray (in females) to black (in males) heads, and rusty red breasts. Many people express surprise to see robins in the winter, but we do have them in southwestern Pennsylvania all year. They are a migratory species, but some birds opt to stay far north. Why is this, if there are much more abundant food resources farther south, especially for a frugivorous/insectivorous bird like the robin? It is a tradeoff – birds that winter farther north may encounter lower food resources and adverse weather conditions, but those that survive the winter are already in place to claim the very best breeding territories. So, seeing robins in the winter is a sign that there are likely decent food resources nearby!

In late winter, male American Robins begin to sing their cheerful, caroling song (cheerily cheer-up cheerio.), a sure harbinger of springtime for many. The early chorus continues through spring, into summer. It is one of the first birds to sing in the morning, often beginning well before dawn, and one of the last to be heard at night. In addition, this species has a variety of distinctive calls, including a shrill cheep alarm call and a low tuktuktuk when disturbed.

Robins are large with dark gray-brown backs and wings, gray (in females) to black (in males) heads, and rusty red breasts. Many people express surprise to see robins in the winter, but we do have them in southwestern Pennsylvania all year. They are a migratory species, but some birds opt to stay far north. Why is this, if there are much more abundant food resources farther south, especially for a frugivorous/insectivorous bird like the robin? It is a tradeoff – birds that winter farther north may encounter lower food resources and adverse weather conditions, but those that survive the winter are already in place to claim the very best breeding territories. So, seeing robins in the winter is a sign that there are likely decent food resources nearby!

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020a, June 24). American Robin. https://abcbirds.org/bird/american-robin/

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Yeray Seminario / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML)

- Female: Gary Mueller / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML261923961)

- Juvenile: Laure Wilson Neish / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML252414801)

- Nest/Eggs: Kristen Johnson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML246196111)

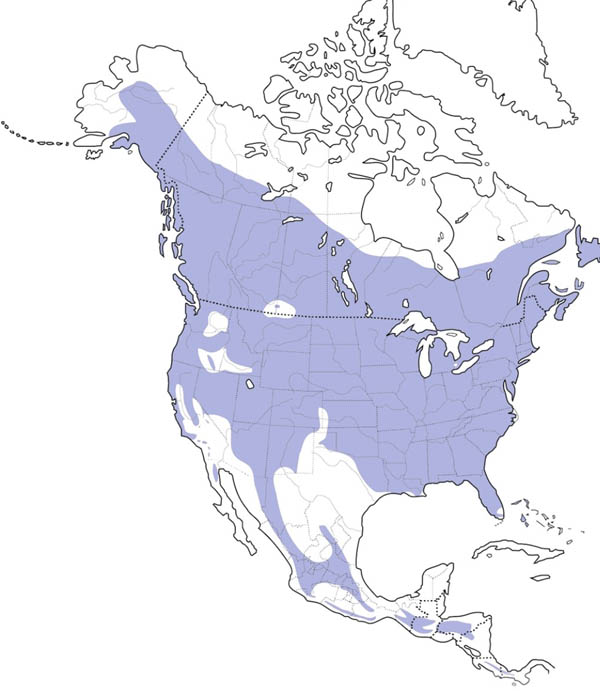

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about American Tree Sparrow

American Tree Sparrow

Spizelloides arborea

This sparrow nests and winters farther north than any of its close relatives. Despite the name, it is not particularly associated with trees, and many of its nesting areas are on the tundra north of the tree line. In winter in the northern states, flocks of Tree Sparrows are common in open country. They often come to bird feeders with Dark-eyed Juncos and other birds. Males may begin singing their musical songs in late winter before they start their northward migration.

Chipping and Tree Sparrows are very similar but check out the eye stripe on both – on the American Tree Sparrow, it is rufous. Tree Sparrows have a bicolored bill (black upper mandible, yellow lower mandible) and have a "tie tack" in the center of the breast. One of the last migratory songbirds we see in fall is the American Tree Sparrow, and its arrival is a sure sign that winter is here.

Chipping and Tree Sparrows are very similar but check out the eye stripe on both – on the American Tree Sparrow, it is rufous. Tree Sparrows have a bicolored bill (black upper mandible, yellow lower mandible) and have a "tie tack" in the center of the breast. One of the last migratory songbirds we see in fall is the American Tree Sparrow, and its arrival is a sure sign that winter is here.

Sources:

- American Tree Sparrow. (2019, October 11). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/american-tree-sparrow

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Cathy Pasterczyk / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML381005601)

- Female: Cathy Sheeter / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML382507671)

- Juvenile: Josiah Verbrugge / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML289412001)

- Nest/Eggs: Micah Grove / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML173587711)

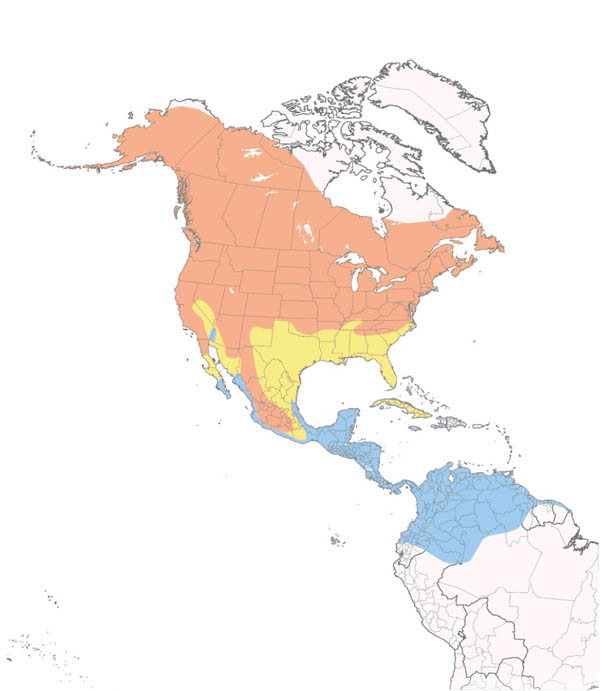

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about American Wigeon

American Wigeon

Mareca americana

While most ducks spend most of their time in the shallows, American Wigeon spends much of their time in flocks grazing on land. Ironically, they also spend more time on deep-water than other marshes, where they get much of their food by stealing it from other birds such as coots or diving ducks. This duck was once named 'Baldpate' because of its white crown.

Sources:

- American wigeon. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/american-wigeon

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Ken Schneider / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML368871671)

- Female: Carol Delynko / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML364106681)

- Juvenile: Josiah Verbrugge / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML289412001)

- Nest/Eggs: Micah Grove / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML173587711)

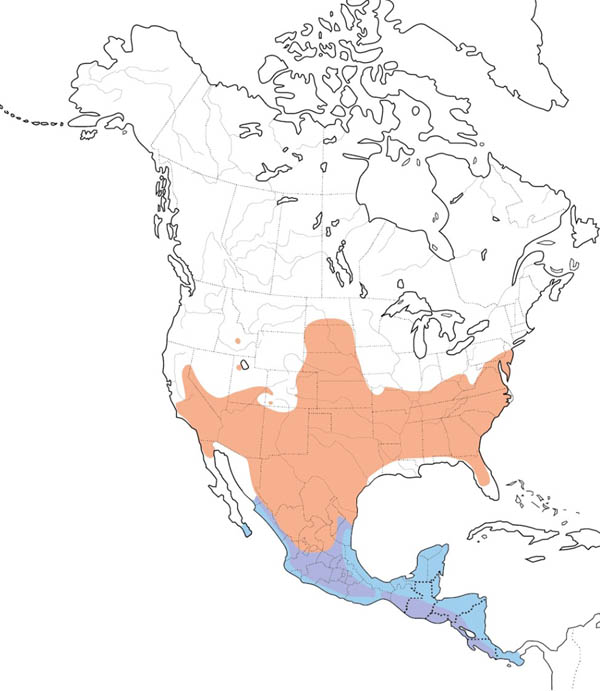

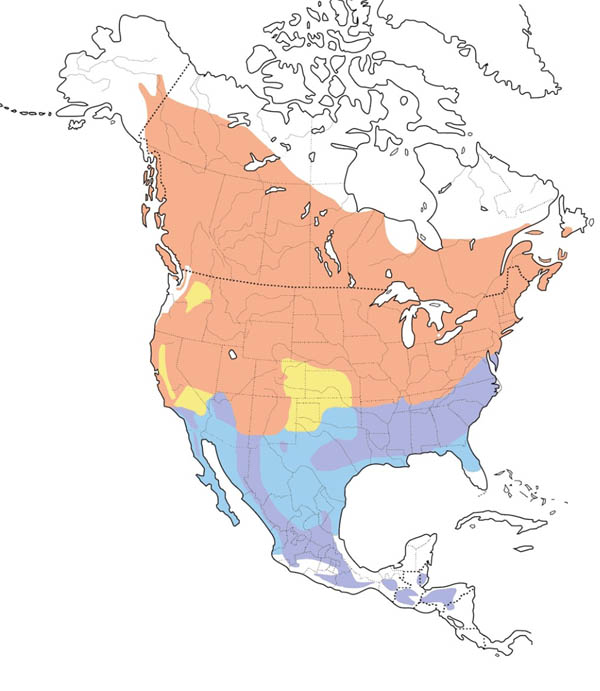

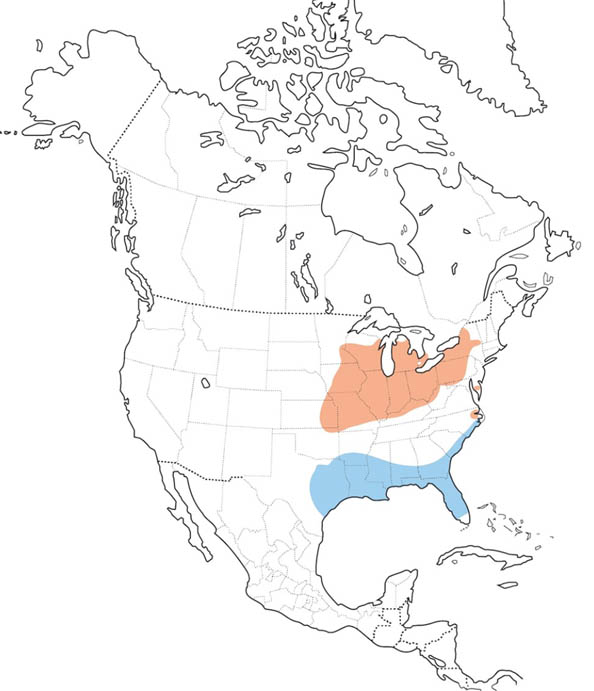

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

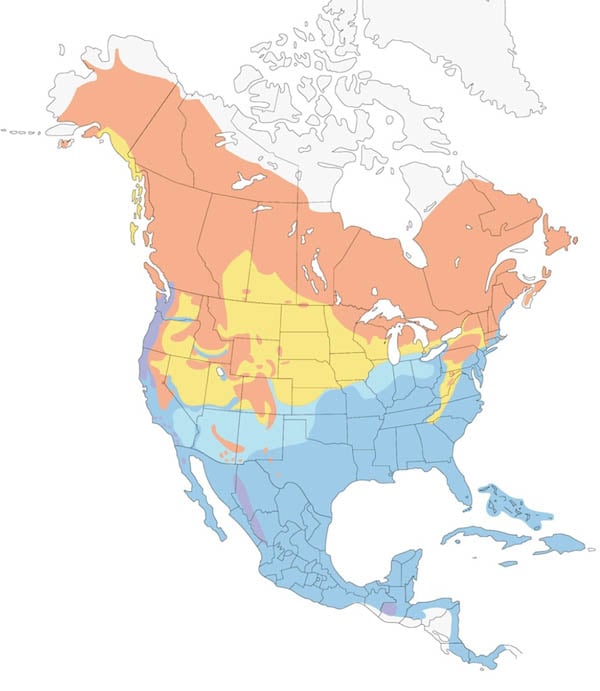

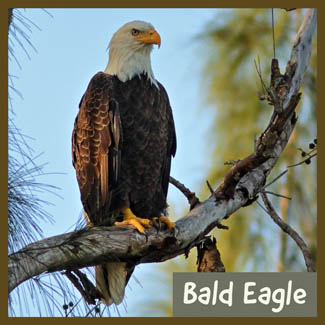

Click here to lean more about Bald Eagle

Bald Eagle

Haliaeetus leucocephalus

The emblem bird of the United States, majestic in its appearance. It is not always so majestic in habits: it often feeds on carrion, including dead fish washed up on shore, and it steals food from Ospreys and other smaller birds. At other times, however, it is a powerful predator. Seriously declining during much of the 20th century, the Bald Eagle has made a comeback in many areas since the 1970s. Big concentrations can be found wintering along rivers or reservoirs in some areas.

Sources:

- Bald eagle. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/bald-eagle

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Yeray Seminario / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML270098301)

- Female: Gary Mueller / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML261923961)

- Juvenile: Laure Wilson Neish / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML252414801)

- Nest/Eggs: Kristen Johnson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML246196111)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Baltimore Oriole

Baltimore Oriole

Icterus galbula

The eye-catching orange and black plumage of the Baltimore Oriole echoes the colors on the coat of arms of England's Baltimore family, some of the first administrators of the state of Maryland. The species is Maryland's state bird and the namesake of its pro baseball team.

The Baltimore Oriole is a member of the blackbird family, so is related to Red-winged Blackbird. Habitat loss on breeding and wintering grounds, pesticide use, outdoor cats, and collisions with glass and towers are the chief threats to this species.

Baltimore Orioles commonly breed in southwestern Pennsylvania, although sometimes they are hard to spot because they tend to stay high in trees where they build pendulum-shaped nests. They will readily come to feeders with fresh orange halves, grape jelly, and nectar, especially during migrations or after young have fledged.

During the breeding season, Baltimore Orioles voraciously feed on caterpillars (even hairy ones that many other bird species avoid!), insects, and spiders. They forage while moving through the treetops, gleaning from leaves and branches, and even picking insects from spider webs. By feeding on large quantities of larvae and insects, the Baltimore Oriole protects trees from extensive damage, providing a valuable ecological service. In the fall and winter, they switch diets from insects to fruit and, interestingly, seem to prefer dark-colored fruit like mulberries and black cherries.

The Baltimore Oriole is a member of the blackbird family, so is related to Red-winged Blackbird. Habitat loss on breeding and wintering grounds, pesticide use, outdoor cats, and collisions with glass and towers are the chief threats to this species.

Baltimore Orioles commonly breed in southwestern Pennsylvania, although sometimes they are hard to spot because they tend to stay high in trees where they build pendulum-shaped nests. They will readily come to feeders with fresh orange halves, grape jelly, and nectar, especially during migrations or after young have fledged.

During the breeding season, Baltimore Orioles voraciously feed on caterpillars (even hairy ones that many other bird species avoid!), insects, and spiders. They forage while moving through the treetops, gleaning from leaves and branches, and even picking insects from spider webs. By feeding on large quantities of larvae and insects, the Baltimore Oriole protects trees from extensive damage, providing a valuable ecological service. In the fall and winter, they switch diets from insects to fruit and, interestingly, seem to prefer dark-colored fruit like mulberries and black cherries.

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020a, June 19). Baltimore Oriole. https://abcbirds.org/bird/baltimore-oriole/

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

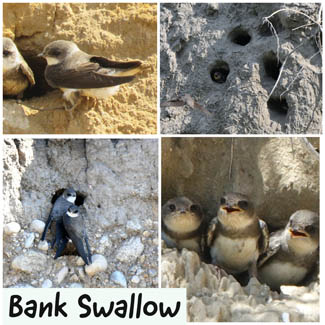

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Howard Lorenz / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML81885211)

- Female: Charles Hundertmark / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML226287971)

- Juvenile: Lisa Hug / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML252697791)

- Nest/Eggs: Alexandre Terrigeol / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML248696531)

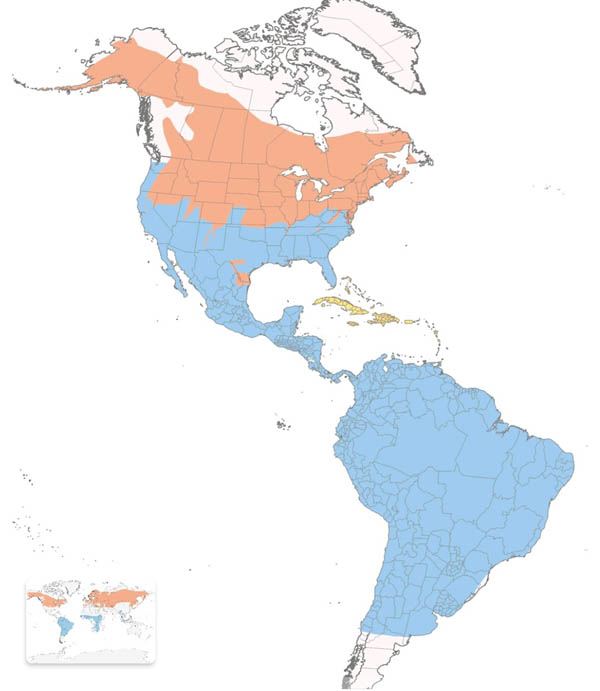

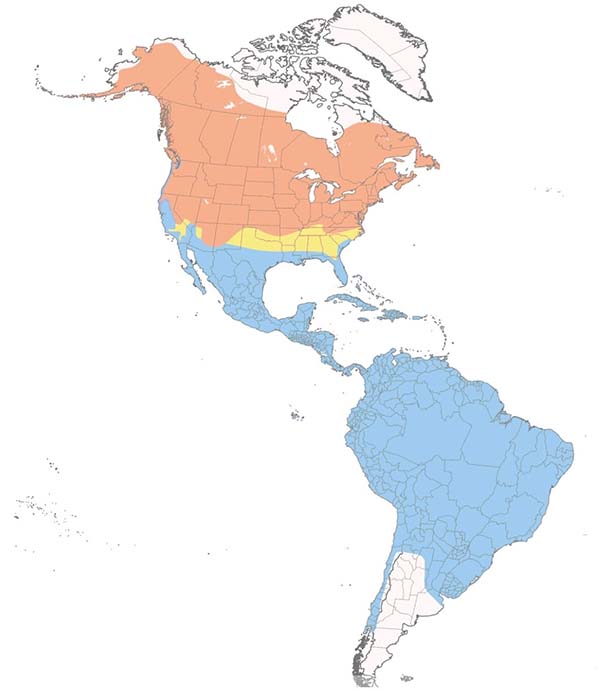

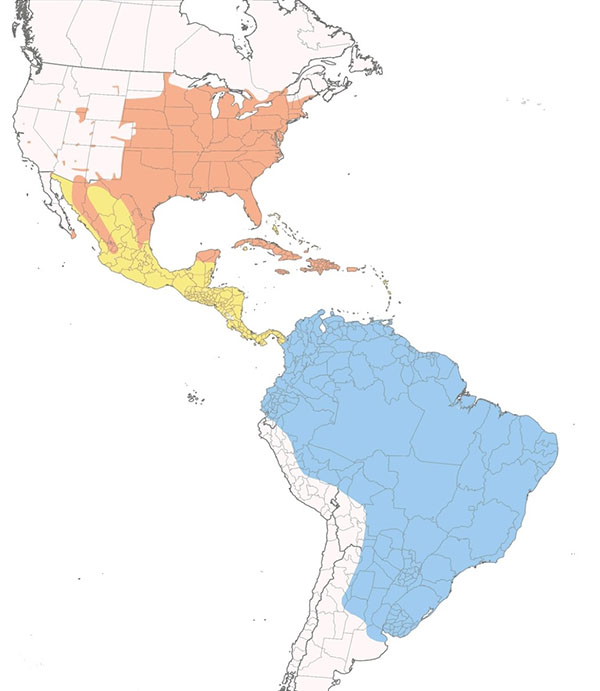

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

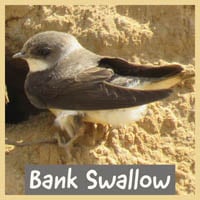

Click here to lean more about Bank Swallow

Bank Swallow

Riparia riparia

The Bank Swallow is a small insectivorous songbird with brown upperparts, white underparts, and a distinctive dark breast band. It is distinguishable in flight from other swallows by its quick, erratic wing beats and its almost constant buzzy, chattering vocalizations. The species is highly social at all times of the year and is conspicuous at colonial breeding sites where it excavates nesting burrows in eroding vertical banks.

The smallest of the swallows, the Bank Swallow is usually seen in flocks, flying low over ponds and rivers with quick, fluttery wingbeats. It nests in dense colonies, in holes in dirt or sandbanks. Some of these colonies are quite large, and a tall-cut bank may be pockmarked with several hundred holes. Despite their small size, tiny bills, and small feet, these swallows generally dig their nesting burrows, sometimes up to five feet long.

The smallest of the swallows, the Bank Swallow is usually seen in flocks, flying low over ponds and rivers with quick, fluttery wingbeats. It nests in dense colonies, in holes in dirt or sandbanks. Some of these colonies are quite large, and a tall-cut bank may be pockmarked with several hundred holes. Despite their small size, tiny bills, and small feet, these swallows generally dig their nesting burrows, sometimes up to five feet long.

Sources:

- Bank Swallow. (2019, October 22). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/bank-swallow

- Species profile: Bank Swallow. (2017, August 24). Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://wildlife-species.canada.ca/species-risk-registry/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=1233

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Michael Stubblefield / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML273394151)

- Female: Adele Wilson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML245538931)

- Juvenile: A Emmerson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML273980361)

- Nest/Eggs: Melody Walsh / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML29725741)

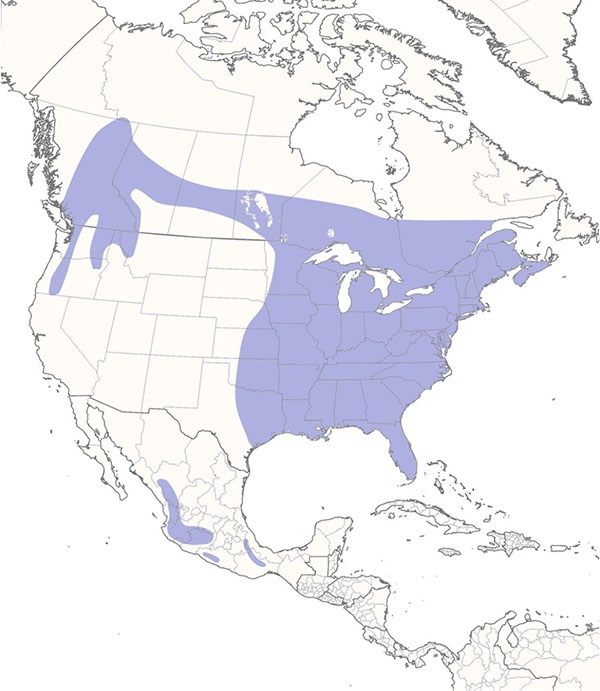

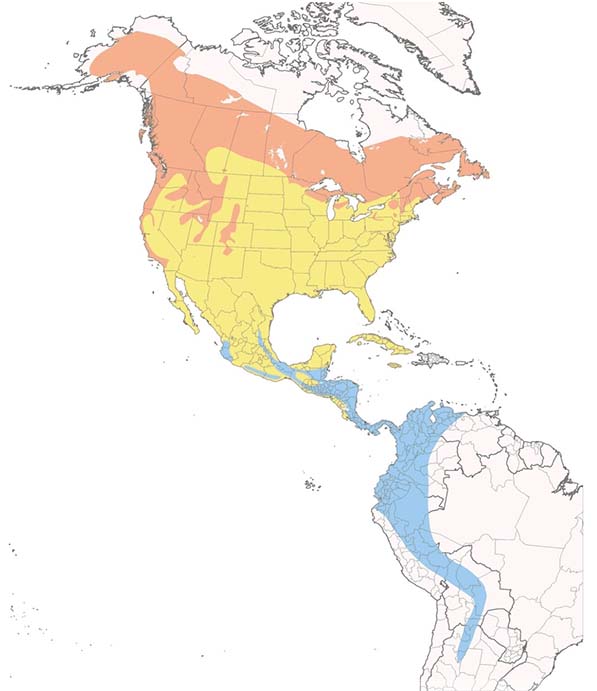

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Barn Swallow

Barn Swallow

Hirundo rustica

Adult male Barn Swallows have a deep iridescent blue crown, back, rump, and wing coverts; deeply forked tail with large white spots; and a rich buff to rufous forehead and underparts. He also has iridescent blue patches on the sides of the breast, sometimes with a very narrow connection in the center. His wings and tail are black. The adult female Barn Swallow appearance is like the male but with paler underparts and a less deeply forked tail.

This metallic-blue-backed "country swallow" — a literal translation of its Latin name — is a familiar sight on farms and in other rural habitats around the world. No other swallow in North America shows such a deeply forked tail. Shorter-tailed juveniles in flight may suggest the Tree Swallow but will always show partial dark breast band and buff throat, white spots on the tail. This distinctive feature is associated with interesting folklore: A Barn Swallow stole fire from the gods to bring it to the people on Earth. One particularly angry god threw fire arrows at the swallow as it fled, singeing off the middle of its tail. The result was the Barn Swallow's distinctive, fork-tailed profile!

This metallic-blue-backed "country swallow" — a literal translation of its Latin name — is a familiar sight on farms and in other rural habitats around the world. No other swallow in North America shows such a deeply forked tail. Shorter-tailed juveniles in flight may suggest the Tree Swallow but will always show partial dark breast band and buff throat, white spots on the tail. This distinctive feature is associated with interesting folklore: A Barn Swallow stole fire from the gods to bring it to the people on Earth. One particularly angry god threw fire arrows at the swallow as it fled, singeing off the middle of its tail. The result was the Barn Swallow's distinctive, fork-tailed profile!

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020b, June 24). Barn Swallow. https://abcbirds.org/bird/barn-swallow-3/

- Barn swallow: National Geographic. (2006). Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/birds/facts/barn-swallow

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Eric Seyferth / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML323373201)

- Female: Richard Mckay / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML347785671)

- Juvenile: maggie s / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML361956311)

- Nest/Eggs: Jack & Holly Bartholmai / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML145747951)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Barred Owl

Barred Owl

Strix varia

The rich baritone hooting of the Barred Owl is a characteristic sound in southern swamps, where members of a pair often will call back and forth to each other. Although the bird is mostly active at night, it will also call and even hunt in the daytime. Only a little smaller than the Great Horned Owl, the Barred Owl is markedly less aggressive, and competition with its tough cousin may keep the Barred out of more open woods.

Sources:

- Barred owl. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/barred-owl

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Karen Lebing / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML360567781)

- Female: Céline Roberge / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML380761261)

- Juvenile: Stephen Davies / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML353712451)

- Nest/Eggs: Samuel Burckhardt / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML330747601)

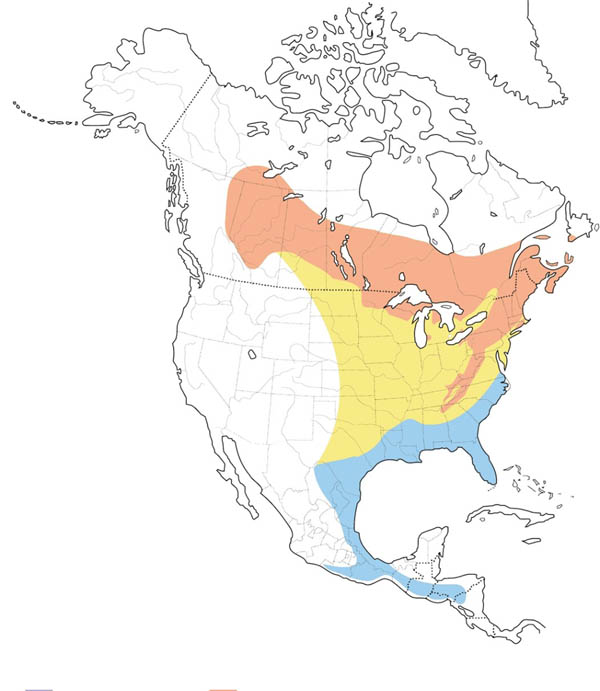

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Belted Kingfisher

Belted Kingfisher

Megaceryle alcyon

One of the most punk-rock bird hairdos in North America is that of the Belted Kingfisher. This species simultaneously looks like it needs a comb, but also looks so very good without a comb! The Belted Kingfisher is often first noticed by its wild rattling call as it flies over rivers or lakes. It may be seen perched on a high snag, or hovering on rapidly beating wings, then plunging headfirst into the water to grab a fish. Kingfishers have narrow heads and heavy beaks with backward serrations that help hold onto the fish they catch and direct them down their throats. Kingfishers are streamlined to maximize aerial fishing efficiency. They're so effective that engineers have used the shape of kingfishers, especially their bills, to design faster and more efficient high-speed trains!

Found almost throughout North America at one season or another, it is the only member of its family to be seen in most areas north of Mexico. Did you know that Belted Kingfishers regurgitate undigestible bits of food, just like owls? Female kingfishers have a bit more color than males: whereas both sexes have a steely blue breast band, females have a rufous cummerbund.

Found almost throughout North America at one season or another, it is the only member of its family to be seen in most areas north of Mexico. Did you know that Belted Kingfishers regurgitate undigestible bits of food, just like owls? Female kingfishers have a bit more color than males: whereas both sexes have a steely blue breast band, females have a rufous cummerbund.

Sources:

- Belted kingfisher. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/belted-kingfisher

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Jim Stasz / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML244593151)

- Female: G & B / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML155968971)

- Juvenile: Michel Laquerre / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML250986321)

- Nest/Eggs: Nest/Eggs: Joyce Wagner / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML27756301)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Black-capped Chickadee

Black-capped Chickadee

Poecile atricapillus

The feisty Black-capped Chickadee is the most common and widespread of the seven chickadee species found in North America. Named for its call and trademark black cap, this little bird is a common sight at backyard bird feeders, along with species such as the Northern Cardinal, Pine Siskin, and American Goldfinch. "Springs here!" or "Hey sweetie!" are common mnemonic devices birders use to remember chickadee songs!

Each fall, Black-capped Chickadees gather and store large supplies of seeds in many different places – an adaptation that helps them to survive harsh winters. But how do they remember where they stash their supplies of seed?

Scientists have shown that Black-capped Chickadees can increase their memory capacity each fall by adding new brain cells to the hippocampus, the part of the brain that supports spatial memory. During this time, the chickadee's hippocampus expands in volume by around 30 percent! In the spring, when feats of memory are needed less, its hippocampus shrinks back to normal size. This phenomenon also occurs in other food-storing songbirds, including jays, nutcrackers, and nuthatches.

This remarkable plasticity is related to hormonal changes in the birds' brains. Scientists are studying this ability in the hopes of eventually helping humans suffering from memory loss.

Each fall, Black-capped Chickadees gather and store large supplies of seeds in many different places – an adaptation that helps them to survive harsh winters. But how do they remember where they stash their supplies of seed?

Scientists have shown that Black-capped Chickadees can increase their memory capacity each fall by adding new brain cells to the hippocampus, the part of the brain that supports spatial memory. During this time, the chickadee's hippocampus expands in volume by around 30 percent! In the spring, when feats of memory are needed less, its hippocampus shrinks back to normal size. This phenomenon also occurs in other food-storing songbirds, including jays, nutcrackers, and nuthatches.

This remarkable plasticity is related to hormonal changes in the birds' brains. Scientists are studying this ability in the hopes of eventually helping humans suffering from memory loss.

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020c, June 24). Black-capped Chickadee. https://abcbirds.org/bird/black-capped-chickadee/

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: fernando Burgalin Sequeria / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML276623801)

- Female: Michael Stubblefield / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML275854991)

- Juvenile: Laurent Bédard / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML257480411)

- Nest/Eggs: Kristof Zyskowski / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML191977071)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Black-throated Green Warbler

Black-throated Green Warbler

Setophaga virens

In the east, some of the easiest warbler voices to recognize are the patterned songs of the Black-throated Green. As if to confirm the identification, the brilliantly colored male often perches out in the open to sing, perhaps on a high twig of a spruce. He has two song types, used in different situations: he sings zoo zee zoo zoo zee to proclaim and defend his nesting territory, and zee zee zee zoo zee in courtship or when communicating with his mate.

When fall migration is here and continues into November, it the time to start watching for birds you only get to see during migration. Black-throated Green Warblers breed at higher elevations in the area (e.g., Laurel Mountain) and can be readily found during both spring and fall migrations.

When fall migration is here and continues into November, it the time to start watching for birds you only get to see during migration. Black-throated Green Warblers breed at higher elevations in the area (e.g., Laurel Mountain) and can be readily found during both spring and fall migrations.

Sources:

- Black-throated Green Warbler. (2019, November 4). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/black-throated-green-warbler

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Larry Theller / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML214836881)

- Female: Richard Littauer / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML269792001)

- Juvenile: Alena Capek / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML224738771)

- Nest/Eggs: Kristof Zyskowski / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML262270681)

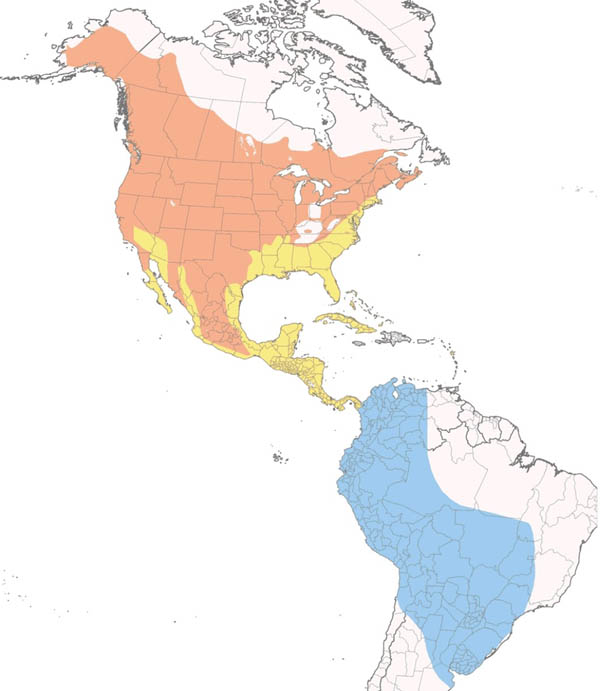

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Black Vulture

Black Vulture

Coragyps atratus

Abundant in the southeast, scarce in the southwest is this broad-winged scavenger. In low flight, it proceeds with several quick flaps followed by a flat-winged glide; when rising thermals provide good lift, it soars very high above the ground. Usually seen in flocks. Shorter wings and tail make it appear smaller than Turkey Vulture but looks are deceptive: body size is about the same, and aggressive Black Vultures often drive Turkey Vultures away from food.

Sources:

- Black Vulture. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/black-vulture

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Seth Honig / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML379380921)

- Female: Kerry Loux / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML379917601)

- Juvenile: Wendy Hill / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML349514241)

- Nest/Eggs: Stephen Paull / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML243143551)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Black-and-white Warbler

Black-and-white Warbler

Mniotilta varia

This bird is often a favorite warbler for beginning birders because it is easy to see and easy to recognize. It was once known as the 'Black-and-white Creeper,' a name that describes its behavior quite well. Like a nuthatch or creeper (and unlike other warblers), it climbs about on the trunks and major limbs of trees, seeking insects in the bark crevices. It often feeds low, and nests even lower, usually on the ground.

Sources:

- Black-and-white warbler. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/black-and-white-warbler

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Lucio 'Luc' Fazio / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML238826521)

- Female: Michael J Good / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML350714361)

- Juvenile: Frédérick Lelièvre / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML354103041)

- Nest/Eggs: Joel Trick / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML250815411)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Black-billed Cuckoo

Black-billed Cuckoo

Coccyzus erythropthalmus

Slipping furtively through leafy thickets, this slim, long-tailed bird is heard more often than seen. It seems even more elusive than the Yellow-billed Cuckoo and is generally seen less often during migration, although the Black-billed is the more common nesting bird toward the north.

These birds are voracious consumers of noxious caterpillars like gypsy moth larvae, eastern tent caterpillar, and fall webworm. The caterpillars’ spines pierce cuckoos’ stomach lining and when it becomes excessive, the stomach lining is sloughed off and regurgitated! Cuckoos also eat cicadas.

These birds are voracious consumers of noxious caterpillars like gypsy moth larvae, eastern tent caterpillar, and fall webworm. The caterpillars’ spines pierce cuckoos’ stomach lining and when it becomes excessive, the stomach lining is sloughed off and regurgitated! Cuckoos also eat cicadas.

Sources:

- Black-billed cuckoo. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/black-billed-cuckoo

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Daniel Pineda Vera / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML371628831)

- Female: John Troth / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML373815541)

- Juvenile: Jackie Elmore / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML262191951)

- Nest/Eggs: / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Blackburnian Warbler

Blackburnian Warbler

Setophaga fusca

A fiery gem of the treetops. In the northern forest in summer, the male Blackburnian Warbler may perch on the topmost twig of a spruce, showing off the flaming orange of his throat as he sings his thin, wiry song. The female also stays high in the conifers, and the nest is usually built far above the ground. Long-distance migrants, most Blackburnians spend the winter in South America, where they are often common in the mountain forests of the Andes.

Sources:

- Blackburnian warbler. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/blackburnian-warbler

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Jim Ferrari / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML379768671)

- Female: Karen Avants / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML375369351)

- Juvenile: Yannick Fleury / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML354140381)

- Nest/Eggs: Ryne Rutherford / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML110206281)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Black-throated Blue Warbler

Black-throated Blue Warbler

Setophaga caerulescens

The lazy, buzzy song of the Black-throated Blue Warbler comes from the undergrowth of leafy eastern woods. Although the bird usually keeps to the shady understory, it is not especially shy; a birder who walks quietly on trails inside the forest may observe it closely. It moves about rather actively in its search for insects, but often will forage in the same immediate area for minutes at a time, rather than moving quickly through the forest like some warblers.

Sources:

- Black-throated blue warbler. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/black-throated-blue-warbler

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Ron Batie / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML265183821)

- Female: Bill Wood / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML269788601)

- Juvenile: Linda Lee / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML255756991)

- Nest/Eggs: Ken Clark / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML257833031)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Blue Grosbeak

Blue Grosbeak

Passerina caerulea

The husky warbling song of the Blue Grosbeak is a common sound in summer around thickets and hedgerows in the southern states. Often the bird hides in those thickets; sometimes it perches up in the open, looking like an overgrown Indigo Bunting, flicking, and spreading its tail in a nervous action. During migration, and in winter in the tropics, Blue Grosbeaks may gather in flocks to feed in open weedy fields.

Any sighting of a blue grosbeak is a cause for celebration, because these beautiful birds just are not that common, and they can be difficult to attract. Although their nesting range covers most of the lower half of the country, spotting one is a rare treat. Look for them in the brush along roadsides and old fields.

These blue birds are sometimes mistaken for Indigo Buntings, another blue Neotropical migrant that arrives at feeders in spring. Warm brown wing bars and a huge bill set blue grosbeaks apart. The female Blue Grosbeak is not blue, but rather a tawny brown!

During the breeding season, they are not backyard birds—unless the backyard includes acres of the shrub-dotted field habitat this species seeks. Nesting season lasts all summer because they often raise two broods. The small nest, often utilizing snakeskins, is built just a few feet off the ground in a bush, briar patch, or tangle of vines. Up to five nestlings may cozy up in the little cup.

Any sighting of a blue grosbeak is a cause for celebration, because these beautiful birds just are not that common, and they can be difficult to attract. Although their nesting range covers most of the lower half of the country, spotting one is a rare treat. Look for them in the brush along roadsides and old fields.

These blue birds are sometimes mistaken for Indigo Buntings, another blue Neotropical migrant that arrives at feeders in spring. Warm brown wing bars and a huge bill set blue grosbeaks apart. The female Blue Grosbeak is not blue, but rather a tawny brown!

During the breeding season, they are not backyard birds—unless the backyard includes acres of the shrub-dotted field habitat this species seeks. Nesting season lasts all summer because they often raise two broods. The small nest, often utilizing snakeskins, is built just a few feet off the ground in a bush, briar patch, or tangle of vines. Up to five nestlings may cozy up in the little cup.

Sources:

- Blue Grosbeak. (2020, April 16). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/blue-grosbeak

- Roth, S. (2021, March 12). Get to Know Blue Grosbeaks. Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://www.birdsandblooms.com/birding/bird-species/get-to-know-blue-grosbeaks-and-how-to-attract-them/

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Anthony Watson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML107834731)

- Female: Nehemiah laudermilch / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML178041371)

- Juvenile: Shelley Rutkin / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML256605661)

- Nest/Eggs: West Tennessee Historical Data / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML89957741)

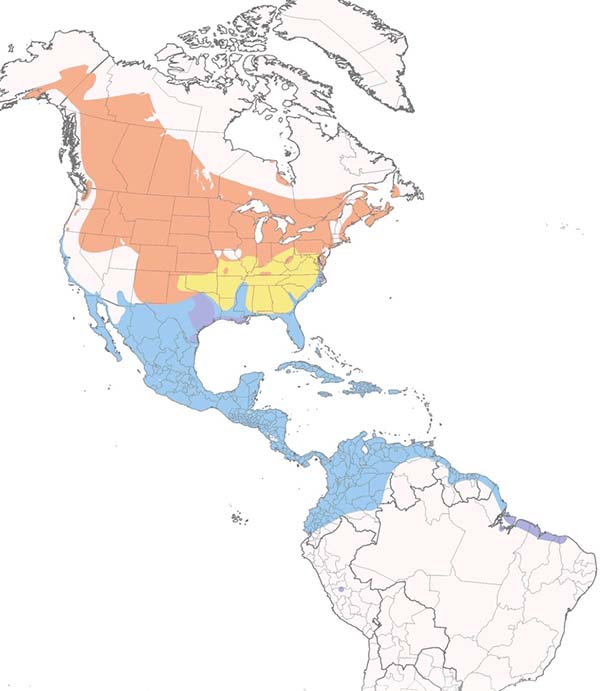

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Blue Jay

Blue Jay

Cyanocitta cristata

The brash and beautiful Blue Jay is seldom regarded with indifference. Some think it is an aggressive bully, while others love its boisterous, sociable nature. A member of the Corvid family, related to the Common Raven and American Crow, the Blue Jay is intelligent and adaptable — qualities that have helped it learn to successfully co-exist with people.

Although not as talented a mimic as Northern Mockingbird or Gray Catbird, a Blue Jay can produce a convincing imitation of Red-shouldered Hawk and Red-tailed Hawk, confusing many a birdwatcher. Blue Jays are known to imitate a variety of other bird species, including the Bald Eagle and Eastern Screech-Owl. This noisy bird also utters a wide variety of squeaks, rattles, and croaks.

Although Blue Jays appear to be brilliantly blue, their feathers are a dull brown. Like the Eastern Bluebird and the Indigo Bunting, their feathers have modified prismatic cells that scatter light waves, reflecting the blue spectrum waves to the viewer.

The Blue Jay is common in much of eastern and central North America, and this adaptable species continues to extend its range to the Northwest. These birds are often quite flashy and vocal in their forest edge and backyard habitats! If you would like to attract more Blue Jays to your backyard, try adding some peanuts to your feeders. According to Cornell's website, they also prefer platform or tray feeders to hanging feeders. They are certainly beautiful birds and often entertaining to watch.

Although not as talented a mimic as Northern Mockingbird or Gray Catbird, a Blue Jay can produce a convincing imitation of Red-shouldered Hawk and Red-tailed Hawk, confusing many a birdwatcher. Blue Jays are known to imitate a variety of other bird species, including the Bald Eagle and Eastern Screech-Owl. This noisy bird also utters a wide variety of squeaks, rattles, and croaks.

Although Blue Jays appear to be brilliantly blue, their feathers are a dull brown. Like the Eastern Bluebird and the Indigo Bunting, their feathers have modified prismatic cells that scatter light waves, reflecting the blue spectrum waves to the viewer.

The Blue Jay is common in much of eastern and central North America, and this adaptable species continues to extend its range to the Northwest. These birds are often quite flashy and vocal in their forest edge and backyard habitats! If you would like to attract more Blue Jays to your backyard, try adding some peanuts to your feeders. According to Cornell's website, they also prefer platform or tray feeders to hanging feeders. They are certainly beautiful birds and often entertaining to watch.

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020e, July 20). American Kestrel. https://abcbirds.org/bird/american-kestrel/

- Maryland birds: American Kestrel. (n.d.). Retrieved May 10, 2021, from https://dnr.maryland.gov/wildlife/Pages/plants_wildlife/American_Kestrel.aspx

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Michael Stubblefield / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML276869391)

- Female: Jonathan Strandjord / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML254129111)

- Juvenile: Suzanne Labbé / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML259936881)

- Nest/Eggs: Jane Thompson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML102318631)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Blue-gray Gnatcatcher

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher

Polioptila caerulea

Blue-gray Gnatcatcher breeds across much of the eastern US and in the southern part of the western US and spends the winter primarily in Florida or Mexico. These are some of the first songbirds that we see migrating in the spring, and we can hear their wheezy song at the beginning of April when there are still plenty of cold, frosty nights.

A very small woodland bird with a long tail, usually seen flitting about in the treetops, giving a short whining call note. Often it darts out in a short, quick flight to snap up a tiny insect in mid-air. Widespread in summer, its breeding range is still expanding toward the north.

A very small woodland bird with a long tail, usually seen flitting about in the treetops, giving a short whining call note. Often it darts out in a short, quick flight to snap up a tiny insect in mid-air. Widespread in summer, its breeding range is still expanding toward the north.

Sources:

- Blue-gray Gnatcatcher. (2019, November 5). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/blue-gray-gnatcatcher

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Margaret Viens / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML178234611)

- Female: Cliff Sanderson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML62327201)

- Juvenile: Michel Laquerre / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML264522541)

- Nest/Eggs: Joe Coppock / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML97167141)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Blue-headed Vireo

Blue-headed Vireo

Vireo solitarius

This vireo is common in summer in mixed forests, where conifers and deciduous trees grow together. When feeding, it works rather deliberately along branches, searching for insects. Its nest, a bulky cup suspended in the fork of a twig, is often easy to find.

The Blue-headed Vireo is recognized by the white "spectacles" around their eyes and their blue-grey head feathers. Blue-headed vireos are summer breeders throughout most of Pennsylvania and overwinter in the far southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

The Blue-headed Vireo is recognized by the white "spectacles" around their eyes and their blue-grey head feathers. Blue-headed vireos are summer breeders throughout most of Pennsylvania and overwinter in the far southern U.S., Mexico, and Central America.

Sources:

- Blue-headed Vireo. (2019, November 5). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/blue-headed-vireo

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Connor Bowhay / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML378713031)

- Female: Richard Rulander / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML380490021)

- Juvenile: Ethan Denton / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML354511811)

- Nest/Eggs: Réjean Deschênes / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML346315521)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Blue-winged Teal

Blue-winged Teal

Spatula discors

Teal are small ducks, fast in flight, flocks twisting and turning in unison. Seemingly a warm-weather duck, the Blue-winged Teal is largely absent from most of North America in the cold months, and winters more extensively in South America than any of our other dabblers. Small groups of Blue-wings often are seen standing on stumps or rocks at the water's edge.

Sources:

- Blue-winged teal. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/blue-winged-teal

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Benjamin Hack / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML250974511)

- Female: Jon Cefus / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML249541581)

- Juvenile: Thomas Schultz / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML172778441)

- Nest/Eggs: Ise Varghese / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML74942851)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Bobolink

Bobolink

Dolichonyx oryzivorus

One aspect of the male Bobolinks is that they have all their faces, chest, belly, wings, and tail colored in black while the shoulders, the lower back, and the rump are somewhere between white and pale gray – whereas the female Bobolinks have underparts colored in yellow and black only in the stripe behind eyes and a little bit on top of their heads.

The bubbling song of the Bobolink ushers in spring across grasslands of the northern United States and southern Canada. Unlike less conspicuous grassland breeders such as the Eastern Meadowlark or Grasshopper Sparrow, the male Bobolink, with his flashy black-and-white breeding plumage, seems to be wearing a "backward tuxedo." No other North American songbird is black underneath and white on the back.

The Bobolink's species name oryzivorus means "rice-eating" and refers to this bird's penchant for grains, particularly during migration and on wintering grounds. When on the move, Bobolink flocks can eat large quantities of grains, and the birds are often shot as agricultural pests, particularly on their wintering grounds. Bobolinks are known as "butter birds" in Jamaica, where the plumped-up migrants are sometimes harvested for food as they pass through that country.

The bubbling song of the Bobolink ushers in spring across grasslands of the northern United States and southern Canada. Unlike less conspicuous grassland breeders such as the Eastern Meadowlark or Grasshopper Sparrow, the male Bobolink, with his flashy black-and-white breeding plumage, seems to be wearing a "backward tuxedo." No other North American songbird is black underneath and white on the back.

The Bobolink's species name oryzivorus means "rice-eating" and refers to this bird's penchant for grains, particularly during migration and on wintering grounds. When on the move, Bobolink flocks can eat large quantities of grains, and the birds are often shot as agricultural pests, particularly on their wintering grounds. Bobolinks are known as "butter birds" in Jamaica, where the plumped-up migrants are sometimes harvested for food as they pass through that country.

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020b, September 18). Bobolink. https://abcbirds.org/bird/bobolink/

- Harp, V. (2015, February 28). Bobolink. Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://www.birdsgallery.net/bobolink/

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: sam hough / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML176079861)

- Female: Susan Disher / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML326332441)

- Juvenile: Byron Stone / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML378093461)

- Nest/Eggs: Nathan DeBruine / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML129115831)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Broad-winged Hawk

Broad-winged Hawk

Buteo platypterus

A small hawk, common in eastern woodlands in summer. Staying around the edges of the forest, Broad-wings are not very noticeable during the breeding season, but they form spectacular concentrations when they migrate. Almost all individuals leave North America in fall, in a mass exodus to Central and South America, and sometimes thousands can be seen along ridges, coastlines, or lake shores when the wind conditions are right.

Sources:

- Broad-Winged Hawk. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/broad-winged-hawk

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Jay Gilliam / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML227279631)

- Female: Elizabeth Leeor / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML54933231)

- Juvenile: Sue Barth / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML252661091)

- Nest/Eggs: Becky Lutz / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML46660261)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Brown Thrasher

Brown Thrasher

Toxostoma rufum

The big, foxy-red Brown Thrasher is a familiar bird over much of the east. Sometimes it forages boldly on open lawns; more often it scoots into dense cover at any disturbance, hiding among the briar tangles and making loud crackling call notes. Although the species spends most of its time close to the ground, the male Brown Thrasher sometimes will deliver its rich, melodious song of doubled phrases from the top of a tall tree.

Eye color can be used to assist in aging some birds, like the Brown Thrasher. Although a paler, creamy gray eye was quite lovely, the adult eye is a bright yellow, often rimmed with an orange-red.

Eye color can be used to assist in aging some birds, like the Brown Thrasher. Although a paler, creamy gray eye was quite lovely, the adult eye is a bright yellow, often rimmed with an orange-red.

Sources:

- Brown Thrasher. (2019, November 18). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/brown-thrasher

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Michael Stubblefield / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML277717561)

- Female: Van Remsen / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML276199231)

- Juvenile: Douglas Faulder / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML261298741)

- Nest/Eggs: Jennifer Wenzel / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML29044361)

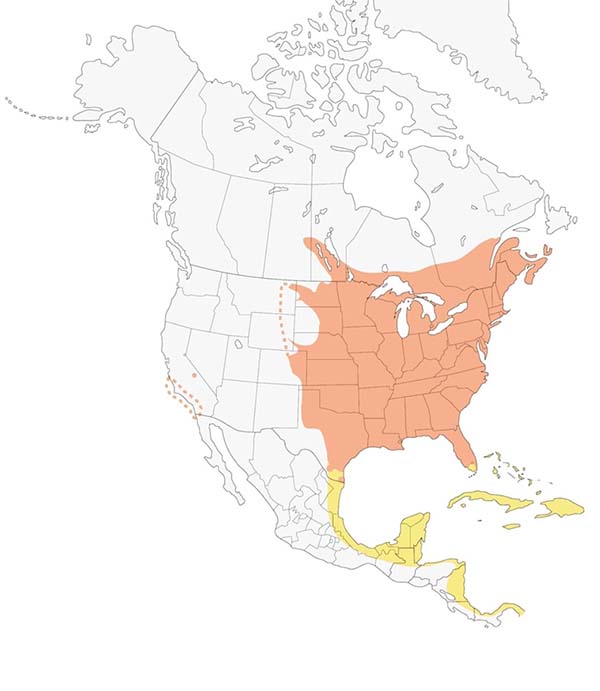

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Brown-headed Cowbird

Brown-headed Cowbird

Molothrus ater

Centuries ago, this bird probably followed bison herds on the Great Plains, feeding on insects flushed from the grass by the grazers. Today it follows cattle and occurs abundantly from coast to coast. The Brown-headed cowbird is a sturdy blackbird with an unusual approach to parenthood. Females do not build nests but use all their energy for producing eggs, sometimes over three dozen per summer. They lay their eggs in other birds' nests, who become their chicks' foster parents, with usually at least some of their foster parents' chicks being victims in the process. Heavy parasitism by this species has pushed some birds to be "endangered" and has affected other populations as well, especially other songbirds.

Sources:

- Brown-headed Cowbird. (2020). Retrieved May 03, 2021, from https://animalia.bio/brown-headed-cowbird

- Brown-headed Cowbird. (2020, February 4). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/brown-headed-cowbird

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Clayton Fitzgerald / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML376488361)

- Female: Jeffrey McCrary / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML357031051)

- Juvenile: Matthew Dudziak / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML365705711)

- Nest/Eggs: Richard André Rivard / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML323815401)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Canada Goose

Canada Goose

Branta canadensis

This big 'Honker' is among our best-known waterfowl. In many regions, flights of Canada Geese passing over in V-formation -- northbound in spring, southbound in fall -- are universally recognized as signs of the changing seasons. Once considered a symbol of wilderness, this goose has adapted well to civilization, nesting around park ponds and golf courses; in a few places, it has even become something of a nuisance. Local forms vary greatly in size, and the smallest ones are now regarded as a separate species, Cackling Goose.

Sources:

- Canada goose. Audubon. (2021, October 20). Retrieved December 15, 2021, from https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/canada-goose

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Michael Stubblefield / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML276870461)

- Female: Bill Wood / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML271385231)

- Juvenile: Gillian Kirkwood / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML212413851)

- Nest/Eggs: James Zipp / www.pixels.com

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Cape May Warbler

Cape May Warbler

Setophaga tigrine

One of those many birds with a puzzling common name, Cape May Warbler does not spend much time in its namesake locale. Instead, Cape May, New Jersey is the place where famed ornithologist Alexander Wilson first described this eye-catching species. As with some other species, the place where the bird was first recorded made for an inaccurate name.

Cape May Warbler is a common migrant that passes through New Jersey en route to its breeding or wintering grounds. Its Latin name, tigrina, is a far more accurate way to describe it, especially the vividly tiger-striped male. Females and juveniles are also striped but in more subdued colors.

We only get to see Cape May Warblers in this area twice each year, during migration - they breed far to the north in Canada's boreal forest and winter mostly on Caribbean islands. It is always a treat to see these birds moving through the trees in a mixed flock of migrating warblers!

Cape May Warbler is a common migrant that passes through New Jersey en route to its breeding or wintering grounds. Its Latin name, tigrina, is a far more accurate way to describe it, especially the vividly tiger-striped male. Females and juveniles are also striped but in more subdued colors.

We only get to see Cape May Warblers in this area twice each year, during migration - they breed far to the north in Canada's boreal forest and winter mostly on Caribbean islands. It is always a treat to see these birds moving through the trees in a mixed flock of migrating warblers!

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020b, June 25). Boreal Breeder: Cape May Warbler. https://abcbirds.org/bird/cape-may-warbler/

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Billy Arimes / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML150626991)

- Female: James Nelson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML278496151)

- Juvenile: Michael O'Brien / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML236788571)

- Nest/Eggs: caleb bronsink / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML94415141)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Carolina Chickadee

Carolina Chickadee

Poecile carolinensis

Very similar to the Black-capped Chickadee, this bird replaces it in the southeastern states. Living in milder climates, it has been reported to be less of a visitor to bird feeders, but it does come into suburban yards for sunflower seeds. Where the ranges of Black-capped and Carolina chickadees come together, they often interbreed. In these contact zones, they also can learn to imitate each other's songs -- causing great confusion for birdwatchers. We are located nearly on a jagged line that extends across much of the eastern half of the US where these two species both occur and often hybridize.

Sources:

- Carolina Chickadee. (2019, November 20). Audubon. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/carolina-chickadee

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Ashlea Veldhoen / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML226589121)

- Female: Gerald Fix / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML260277621)

- Juvenile: valerie heemstra / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML257652521)

- Nest/Eggs: Trevor Palmer / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML219132971)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Carolina Wren

Carolina Wren

Thryothorus ludovicianus

Carolina Wrens are in the area year-round. We often see them visiting the feeders or flitting about in the shrubby areas. They sing their boisterous "teakettle-teakettle-teakettle" song. The Carolina Wren is a familiar backyard bird, like the Northern Cardinal and Downy Woodpecker, although it is more often heard than seen. For those interested in learning how to identify birds by voice, the Carolina Wren provides interesting lessons. Here is one: Although only males sing, the females provide backup. Male Carolina Wrens belt out a loud "tea-kettle tea-kettle tea-kettle" or "cheery-cheery-cheery" and females provide backup with an enthusiastic, drawn-out trill accompanying the song's end.

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2020a, June 24). Carolina Wren. https://abcbirds.org/bird/carolina-wren/

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Kristof Zyskowski / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML161920271)

- Female: Laurent Bédard / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML225911381)

- Juvenile: Pair of Wing-Nuts / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML270849921)

- Nest/Eggs: Christopher Coxson / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML61810201)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

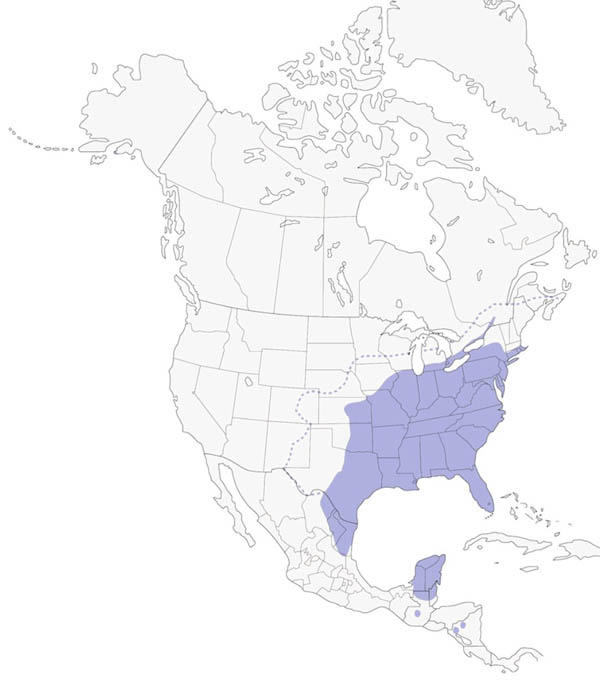

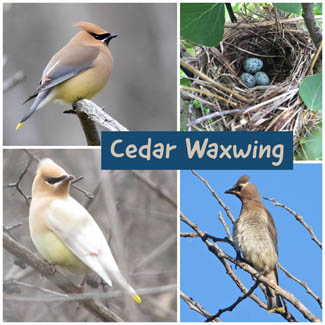

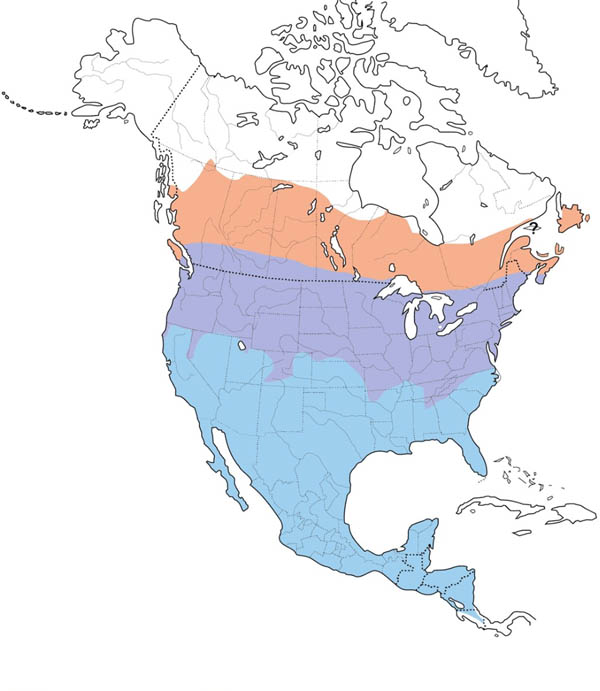

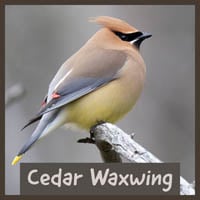

Click here to lean more about Cedar Waxwing

Cedar Waxwing

Bombycilla cedrorum

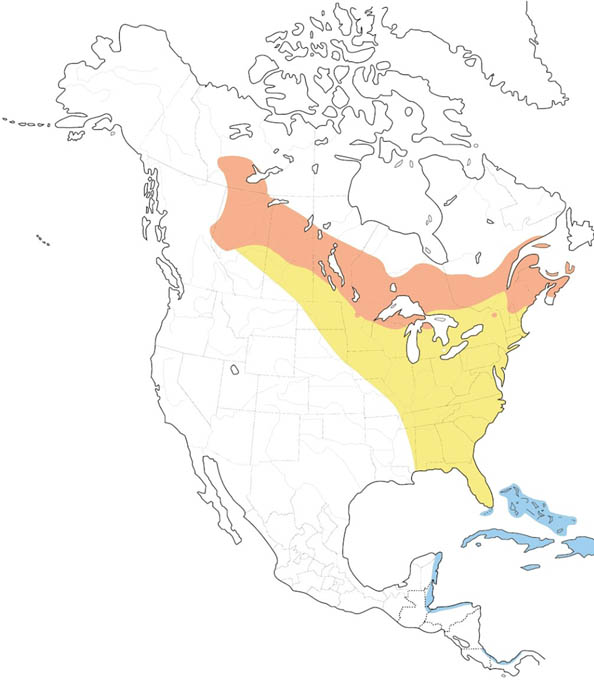

The Cedar Waxwing's genus name, Bombycilla, means "silk-tail" and refers to its dapper-looking plumage. The species name, cedrorum, is Latin for "of the cedars" and reflects its fondness for the small cones of the eastern red cedar.

One of this bird's most distinctive features is the bright-red, waxy tips on its secondary wing feathers, the result of its fruit-heavy diet, although immature birds usually show no red waxy tips. The "wax" tipping the Cedar Waxwing's secondary wing feathers is an accumulation of the organic pigment astaxanthin, a carotenoid that gives red fruits their color. The tips increase in number and size with an individual's age, and immature birds may show no red wingtips at all. Some scientists speculate that waxwings evolved these waxy tips to signal important information — such as age and social status — to other birds within the flock. The waxwing's striking yellow tail tip is also the result of the carotenoids that color the fruit this species loves to eat. In recent years, waxwings eating the fruits of introduced honeysuckle have grown orange-tailed tips instead!

Did you know that you can find Cedar Waxwings in this area all year? They are almost certainly different individuals than those we see in the summer, but they will form small flocks and roam around finding berries to eat all winter. By the late part of winter, some of those berries may have fermented a bit and Cedar Waxwings may get a little tipsy from eating them!

One of this bird's most distinctive features is the bright-red, waxy tips on its secondary wing feathers, the result of its fruit-heavy diet, although immature birds usually show no red waxy tips. The "wax" tipping the Cedar Waxwing's secondary wing feathers is an accumulation of the organic pigment astaxanthin, a carotenoid that gives red fruits their color. The tips increase in number and size with an individual's age, and immature birds may show no red wingtips at all. Some scientists speculate that waxwings evolved these waxy tips to signal important information — such as age and social status — to other birds within the flock. The waxwing's striking yellow tail tip is also the result of the carotenoids that color the fruit this species loves to eat. In recent years, waxwings eating the fruits of introduced honeysuckle have grown orange-tailed tips instead!

Did you know that you can find Cedar Waxwings in this area all year? They are almost certainly different individuals than those we see in the summer, but they will form small flocks and roam around finding berries to eat all winter. By the late part of winter, some of those berries may have fermented a bit and Cedar Waxwings may get a little tipsy from eating them!

Sources:

- American Bird Conservancy. (2019, January 17). Sociable Fruit-Feeder: Cedar Waxwing. https://abcbirds.org/bird/cedar-waxwing/

- Powdermill Nature Reserve, Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Grid (counterclockwise):

- Male: Jim Hully / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML272585391)

- Female: Yannick Fleury / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML253146991)

- Juvenile: Steve Kelling / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML181073391)

- Nest/Eggs: Alyssa DeRubeis / Macaulay Library at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology (ML252274711)

- Range map provided by Birds of the World

Click here to lean more about Chestnut-sided Warbler

Chestnut-sided Warbler

Setophaga pensylvanica

Chestnut-sided Warbler was not well known before the 1800s; prominent ornithologists such as Audubon and Wilson seldom saw the bird and knew little about it. Like the Golden-winged Warbler, this bird nests in semi-open, brushy areas, so could only be found where forest fires and other natural phenomena had created this habitat.

The male Chestnut-sided Warbler sings two song types; one is accented at the end, the other is not. The first is used before the arrival of the females and in the early nesting cycle. The second is used mostly in territory defense while the birds are raising young.

Males that only sing one song type appear to be less successful at attracting mates than males that sing both songs. The early-season song has a musical quality with an emphatic ending, sometimes interpreted as "very very pleased to meet cha!"

The Chestnut-sided Warbler is a common breeder in the woods of Pennsylvania. With a quick look at a Chestnut-sided Warbler, it is easy to see how it got its name - it has chestnut-colored patches on the flanks. But what about its scientific name, Setophaga pensylvania? Setophaga comes from the Greek "ses" which means "moth" and "phagos" which means "eating" - an appropriate genus name for a bird that eats a lot of butterfly and moth larvae. Pensylvanica refers to Pennsylvania, which is also appropriate as Chestnut-sided Warblers are a common breeding bird in the woods of Pennsylvania.

And how about en Español? Chestnut-sided Warblers spend the winter in Mexico and Central America and are known in Spanish as Reinita de Pensilvania which roughly translates to "little queen of Pennsylvania."

The male Chestnut-sided Warbler sings two song types; one is accented at the end, the other is not. The first is used before the arrival of the females and in the early nesting cycle. The second is used mostly in territory defense while the birds are raising young.

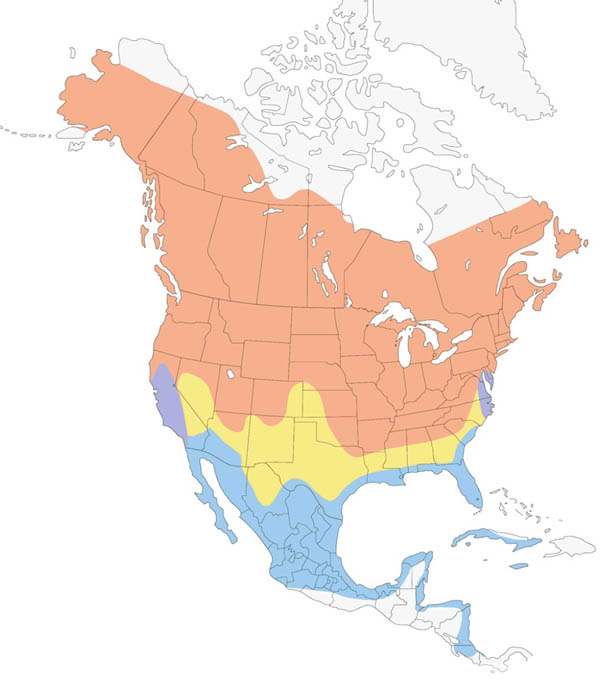

Males that only sing one song type appear to be less successful at attracting mates than males that sing both songs. The early-season song has a musical quality with an emphatic ending, sometimes interpreted as "very very pleased to meet cha!"